|

|

|

|

|

PROJECT CONSTITUTION: May 2021 UPDATE

Protecting the Rule of Law and the Supreme Court of Canada

Court File No.______________ Action FEDERAL COURT BETWEEN: Zoltan Andrew SIMON, ZuanHao ZHONG and Jian Feng YE Plaintiffs

and HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN (in Right of Canada), as represented by the ATTORNEY GENERAL OF CANADA Defendants STATEMENT

OF CLAIM pursuant to subsections 17 (1) and (2)(a)-(d) and ss. 18 (1) of the Federal Courts Act, and ss. 49 and 64 of the Federal Courts Rules STATEMENT OF CLAIM

TO THE DEFENDANT: A LEGAL PROCEEDING HAS BEEN COMMENCED AGAINST YOU by the Plaintiff. The claim made against you is set out in the following pages. IF YOU WISH TO DEFEND THIS PROCEEDING, you or a solicitor acting for you are required to prepare

a statement of defence in Form 171B prescribed by the Federal Courts Rules, serve it on the plaintiff’s solicitor or, where the plaintiff does not have a solicitor, serve it on the plaintiff, and file it, with proof of service, at a local

office of this Court, WITHIN 30 DAYS after this statement of claim is served on you, if you are served within Canada. If you are served in the United States of America, the period for serving and filing your statement of defence is forty days.

If you are served outside Canada and the United States of America, the period for serving and filing your statement of defence is sixty days. Copies of the Federal Courts Rules, information concerning the local offices of the Court and

other necessary information may be obtained on request to the Administrator of this Court at Ottawa (telephone 613-992-4238) or at any local office. IF YOU FAIL TO DEFEND THIS PROCEEDING, judgment may be given against you in your absence and without

further notice to you. Date: Issued by: Address of local office: Canadian Occidental Tower 635 Eighth Avenue S.W., 3rd Floor, P.O. Box 14 Calgary, Alberta, T2P 3M3

TO: The Attorney General of Canada C/O Office of the Deputy Attorney General of Canada 284 Wellington Street Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0H8 Claim - The plaintiff

claims: Orders or declarations for various types of damages exceeding a total of $50,000, inter alia, and/or declaratory relief (or orders declaratory of the rights of the parties) as specified on pages 28 to 34 of the Memorandum of Fact

and Law below, in paragraphs 255-312.

- For each allegation of material fact relied on to substantiate the claim, please refer to paragraphs 1 to 110, from page 4 to page 14 of the Memorandum of Fact and Law below. A concise statement

of the material facts is required but no legislation or case law has defined the word “concise,” except s. 12 of the Interpretation Act and ss. 70 (1) and (4) of the Rules.

- If the Court orders so, the plaintiffs could

amend this claim, converting it into a 1000-page dissertation, listing ca. 70 violations of Canadian law and 15 violations of BC law. The Crown servants’ acts or omissions and the caused damages often overlap. Also, it is hard to assign dollar figures

of damages to Crown policies that place officers of the courts above the Courts. Finally, declaratory relief is available without a cause of action (Manitoba Metis Federation, 2013 SCC), etc.

The plaintiff proposes

that this action be tried at Calgary, in the Province of Alberta, possibly by videoconference or teleconference as the Covid-19 pandemic circumstances allow or dictate. May 28, 2021 Zoltan Andrew SIMON __________________

Signature of main plaintiff) Zoltan Andrew SIMON 72 Best Crescent, Red Deer, Alberta T4R 1H6 Phone: 1-587-306-9825 FAX number: 1-403-341-3300 E-mail: zasimon@hotmail.com

URL: www.correctingworldhistory.com CLAIM: Memorandum of Fact and Law Part I – A concise statement of fact - The

plaintiff has been a Canadian citizen since 1979. He was born in Hungary in 1949 and immigrated in Canada in 1976. He worked in civil engineering in Canada in 1977-1997. He is a security officer in Red Deer since 2008. He is author of several books and papers

published in English, mainly on ancient history and chronology.

- This is an action against the federal Crown for damages for conspiracy and fraudulent misrepresentation, including requests to the Court for declaratory relief.

- All or most of

the facts are and have been in dispute between the two parties.

- On 25 June 2014, A. Brown, Counsel to the AGC submitted to a Court that all of Z. Simon’s 193 allegations of fact were denied, without offering alternative facts.

- On 13

June 2017, A. Brown, Counsel to the AGC submitted to a Court that all of Z. Simon’s 347 allegations of fact were denied, without offering alternative facts.

- On June 23, 2006, the Commissioner (commissaire) of Revenue of the Canada Revenue Agency

and the Deputy Minister of Citizenship and Immigration Canada signed a policy named Memorandum of Understanding, a.k.a. MOU.

- Since 2006, the purpose of this MOU was streamlining the collection of the Crown’s debt claims

related to sponsorship in the family class, by raising MOU and the policy named IP 2 – Processing Applications to Sponsor Members of the Family Class above the IRPA and the IRP Regulations. The Crown obliged its civil

servants to apply them in tandem, to obey them while ignore sections of the IRPA and IRPR.

- The tortious MOU agreement between federal ministers to defeat the legislation for unlawful financial gains satisfies the test for

conspiracy for a dishonest money extortion scheme to defraud the public: R. v. Olan et al., 1978 CanLII 9 (SCC).

- The MOU falsely claims that a “debt arises pursuant to subsection 145 (2) of the Immigration

and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA) with respect to these benefits, which is payable on demand…” A debt arises only if the Crown satisfies a precondition stated in ss. 146 (1) and (2) of the IRPA by filing

a ministerial certificate in the Federal Court. The Supreme Court of Canada has confirmed repeatedly the latter interpretation in Canada (Attorney General) v. Mavi, 2011 SCC 30 (CanLII), [2011] 2 SCR 504.

- The MOU truncates s. 146

of the IRPA, by removing its important heading: “…section 146 of IRPA provides that an amount or part of an amount payable under this Act that has not been paid may be certified by the Minister without delay…, on the expiration

of thirty (30) days after the default. The certificate is to be filed and registered in the Federal Court and when registered, has the same force and effect, and all proceedings may be taken as if the certificate were a judgment obtained in the Court for a

debt.” The removed heading says that if a Minister wants to recover a sponsorship debt, he or she must file and register a ministerial certificate in the Federal Court.

- None of the ministers satisfied this condition precedent

before the seizures.

- The ministers often (or always) fail to file and register such ministerial certificates of debt in the Court. One cannot believe that the intention of CRA and CIC by the introduction of MOU and IP 2 in tandem

was to punish only Z. A. Simon and his sponsored family because in June 2006 he did not yet know his Chinese wife.

- In the case of Z. Simon, despite his repeated requests to federal and provincial (BC) ministers for a copy of such certificate, no minister

has been able to produce such document between 2000 and 2021 because it simply did not exist.

- A BC ministry issued a letter dated 11 October 2012, stating that no record or ministerial certificate was found in that Province regarding Z.A. Simon’s

alleged debt.

- The Federal Court of Appeal, in Simon v. Canada, 2011 FCA 6 (CanLII), overturned Zinn J.’ decision and stated: “… the Canada Revenue Agency improperly paid monies owing to Mr. Simon under the Income Tax

Act to the government of British Columbia, without any notice or explanation to Mr. Simon. There is no suggestion that any garnishment order issued from a court of competent jurisdiction”.

- Since 2011, all Attorneys General of Canada and

counsels to them have completely ignored, disregarded and disobeyed this verdict of the FCA as not binding.

- The MOU claims, “The purpose of this MOU is to delegate the powers of the Minister of Citizenship and Immigration, relating

to sections 146 and 147 of the IRPA, to officials of the CRA for the purpose of recovering outstanding sponsorship debts owing to provinces and territories.” The Minister of CIC, by the contravention of ss. 146(2) of the IRPA,

cannot delegate his non-existing powers to CRA: 1994, c 31, s. 4.

- The MOU and ITA are silent about a section of any Act or legislation, particularly the Income Tax Act, that would allow the Crown/CRA

to seize monies of a taxpayer without a garnishment order issued by a Court, without a “memorial” or “ministerial certificate” on file in a Court. CRA’s seizures are s. 8 Charter violations.

- The

IP 2 policy applied in family class sponsorships contains five times the word “contract”. This fact has been admitted by a Minister of Justice, according to a submission of Ms. Alison Brown during a previous court case (No. 4756, Golden).

- Contrary to the IP 2, ss. 132 (4) of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations is silent about a family class contract: sponsors and co-sponsors must declare to keep an agreement with

the principal sponsored persons, admitting their joint obligations in two statements. Agreements and statements are not contracts.

- The (CIC) Sponsorship Agreement and Undertaking forms emphasize at length the mutual

obligations of both parties. The forms fail to mention that, in practice, the principal debtors (the sponsored immigrants that receive social benefits) are always off the hook without any obligation while the sponsors are punished with cruelty.

- The

Crown is stereotyping by implying that every sponsored immigrant is always innocent, acting in good faith, while their Canadian sponsors are always unreliable and break their promises, so the default is always their fault.

- The above-mentioned CIC

forms clearly state that the Crown may represent the sponsored immigrant at a Court of competent jurisdiction where the defaulting sponsors may be sued for damages. This condition materially induced Z. Simon, as a sponsor, to act to his detriment.

It was a “causa sine qua non” for him in January 1999 when he signed a CIC sponsorship undertaking for Ms. Reyes, a previous spouse.

- She landed in Canada on 27 December 1999 with her two young sons.

- In mid-June 2000,

she wanted to start an independent life, so her sponsor had to move out from his rent-to-own apartment, losing it, and survive separately.

- From October 2000, a ministry of British Columbia paid her social benefits, removing her from the work force,

without informing the sponsor of the amounts paid. They paid her those for 5 years, despite that full time students did not qualify for it.

- The actual garnishment, rather seizure, was made by the Defendant (CRA).

- On 23 of March 2007, S. Postuk,

an officer of a BC ministry issued a false statement on a single page without official heading, alleging that Z. Simon had a debt.

- The page claimed that the debt was enforceable. RCA accepted the falsehood.

- Between October 2000 –

when a default happened – and 2021, the Crown has never taken Z. A. Simon to any court for damages, and never revealed if its damage claim was in contract or in tort. Z.A. Simon tried to get a court order several times, but

it turned out that Canada did not have a court of competent jurisdiction for cases where Crown debts owed to persons simply disappear from their tax credit accounts.

- Both the Federal Court and the Tax Court (2019-07-12) declined jurisdiction in a

case where CRA determined a credit amount correctly as a subtotal, but the amount disappears without a lawful explanation in the last line of the Notice(s) of Assessment.

- This is a real live controversy between the parties involving questions of law.

- The FC has power to grant declaratory relief to clarify real issues or questions.

- The Crown applies the principle of “divide and conquer” by creating two sets of rules, conditions, and obligations: one for its public servants, and

a different one for sponsors in family class immigration. CRA reaps a windfall and sends the seized laundered monies to the provinces as gifts after the seizure of non-existing debts.

- Following this federal money extortion scheme punishing the re-victimized

sponsors in the family class, the second federal tort is related to Guide 3900 and Form IMM 1344. Both were published by CIC, the federal Ministry of Citizenship and Immigration represented by the Defendant in 2015 and the following years.

- In January 2016, Z. Simon reported this problem to Minister John McCallum.

- On 16 March 2016, an unnamed visa officer in Hong Kong, of the Immigration Section of our Consulate General, heard his wife and refused her immigration again.

- After

9 years of good marriage, she accused us, maybe coerced by the Minister, that our marriage was not genuine under subsection 4 (1) of the IRP Regulations.

- The first refusal happened on 25 April 2007 by visa officer A. Chau

in Hong Kong, based on ss. 133(1)(g)(i) of the IRPR. He did not refer to its ss. 4(1) at all.

- Similarly, not a word of suspicion was uttered about a bad faith marriage on behalf of Crown Counsel Mr. Statikos

or Ms. Kashi Mattu IAD Tribunal on 13 August 2009, or in her IAD decision. The latter, dated 17 November 2009 goes, “the panel is making the implicit assumption that the applicant is a member of the family class …”

- Pages 23-25 of

CBSA’s book (2007-10-20, Toronto) mentions the return of a DVD to Z.A. Simon (a video made during our wedding reception on 24 December 2006 in Guangzhou City), referring to our “original relationship documents” as well.

- In 2007,

Z. Zhong wanted to get a baby from Z. Simon, a fact he mentioned at the IAD hearing. Now that child would speak only Cantonese, separated from him.

- Visa Officer 2’s decision of 24March 2016 guessed that Z. Simon and his wife were incompatible

with a 13-year age gap since belonged to different cultures, nations and religions and did not have a common language, so IRPG’s ss. 4 (1) applied.

- The hearing was procedurally unfair to Z. Zhong since the Visa Officer

did not allow the hired interpreter to speak during most of the hearing. She heard Ms. Zhong by “telepathy” who was at a total loss to understand the questions in English. Her son Mr. Ye was not allowed to enter the hearing room: he had to wait

outside. This ended up in the CAIPS notes as: [Is your son here?] “No, he needs to go work today.” These unusual and cruel circumstances constitute section 12 and 14 Charter infringements.

- Well

before the 2018 IAD haring, Z. Simon wanted to call a witness, a niece, under ss. 37(1) of the IAD Rules. Mr. Tucci, the Panel, refused to hear her testimony as unnecessary. Also, he refused to consider the affidavits of three persons

properly submitted under ss. 43(3) of those IAD Rules. These constituted procedural unfairness.

- The reasons of Mr. Tucci’s IAD decision following the 4 July 2018 hearing would not only fly in the face of common sense

and reasonability, inviting ridicule, but it constitutes a total disregard of the obvious intent of Parliament to provide for the families’ reunification in Canada in ss. 3 (1) (d) of the IRPA and in the Charter.

- One of his main reasons to suggest Z. Simon’s bad faith marriage with Ms. Zhong in 2006 was that, as her sponsor, he kept sending her monies in 2016-18 despite her testimony for IAD that generally she was able to survive by her own work.

- Canadian husbands have no obligation to supervise their wives’ finances.

- A lack of Z. Simon’s financial control over Ms. Zhong in 2016-2018 could not have been a “causation” for Ms. Zhong’s motivation to marry Z.

Simon in 2006.

- Since 2007, none of AGCs has disclosed a section of a law under which the Crown kept seizing the tax credit monies of the plaintiff, apparently as ransom.

- Since 2011, none of them have been able to substantiate their routine

false or sweeping allegations – as a broken record – regarding debt, the vexatious, frivolous, res judicata, and abuse of process nature of Z.A. Simon’s submissions to the courts.

- Since 2007, none of those counsels to the

Attorneys General have been able to refer to a definite section or paragraph of a specific court order or decision as a “final judgment” as defined in s. 2 (1) of the Federal Courts Act, since

there was none.

- For 14 years, the best judges of the FC, TCC and the FCA have been unable to pinpoint any radical error, fatal flaw or incurable defect in Z.A. Simon’s submissions.

- All courts have carefully

avoided to address the question of the parties’ rights.

- To a certain degree, this fact vindicates the integrity of every justice. All of them had the power and jurisdiction to declare that the Crown can seize such monies without the involvement,

order, or filed certificate of a Court, but none of them did so.

- Since June 18, 2012 – the response of the Crown written by Wendy Bridges – till Mr. K. Sinnott counsels to AGC habitually submitted sweeping or false allegations, half-truth

and “white lies” to federal or provincial courts in BC and Alberta.

- The courts had no time to apply the plain and obvious test but simply echoed such misleading statements, causing a domino effect that three courts declared Z.A.

Simon a vexatious litigant. Falsehood repeated ad nauseam does not become true.

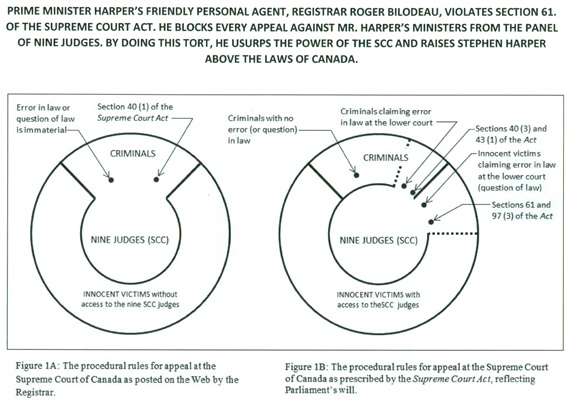

- As for the habitual or repeated torts of the employees of the SCC Registry in Ottawa and their contraventions of section 61 of the Supreme

Court Act, RSC 1985, ss. 19(2)(a) and 32(1)(a) of the Rules of the Supreme Court of Canada, and s. 139 (2) of the Criminal Code, the following employees have been involved, based on

their unlawful actions or omissions revealed by their letters sent to Z.A. Simon as follow:

- Barbara Kincaid’s letter to Z.A. Simon dated 2012-05-24.

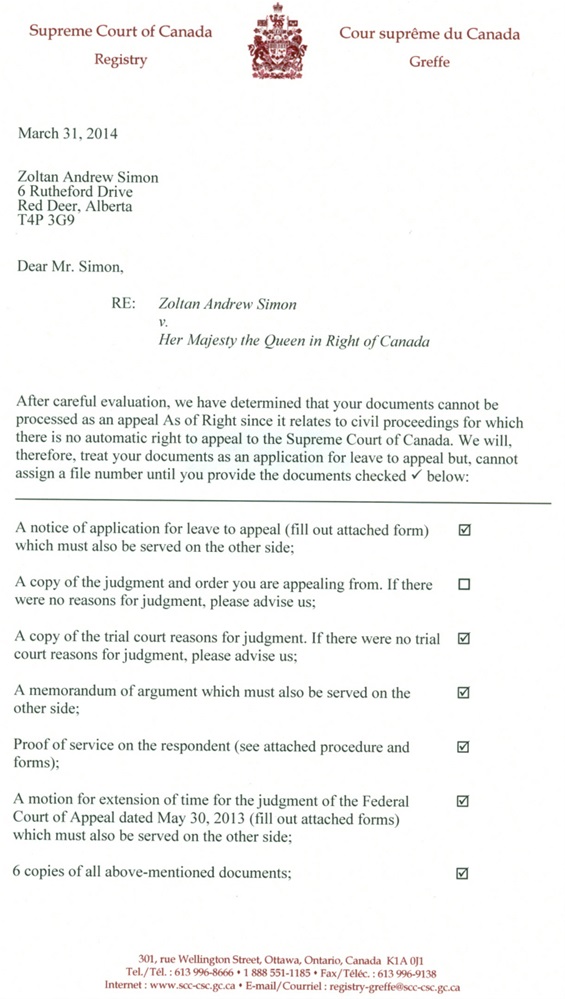

- Mary Ann Achakji’s letter: 2012-03-28; Nathalie Beaulieu’s ca.

2014-03-31.

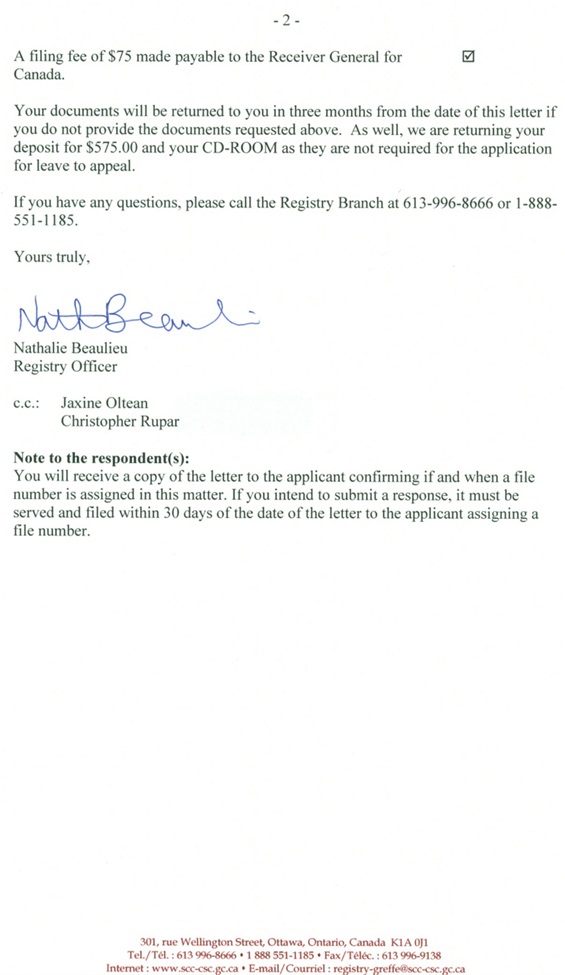

- R. Bilodeau’s letters to Z.A. Simon dated 2012-12-18, 2014-08-14, 2016-03-10, and 2016-04-12 denied filing his 3 notices of appeal under s. 61 ofthe SCC Act.

- He treated one as an application.

A 3-juctice panel dismissed it on 2012-10-04.

- Z.A. Simon requested the SCC to reconsider it but on 18 December 2012 the Registrar, Mr. Roger Bilodeau, dismissed his motion in a private letter, not in an order.

- A motion of Z.A. Simon’s

to SCC was dismissed on September 16, 2014.

- The letters of Ms. Achakji and Ms. Beaulieu show that employees of the SCC Registry in Ottawa, as “we”, discussed the possibility of obeying s. 61 of the Act but they

rejected it: an indication of an agreement to conspire or contravene the Act.

- SCC Registrar R. Bilodeau has successfully obstructed, perverted or defeated the course of justice on seven counts between 2012 and 2020, by repeatedly preventing

Z.A. Simon from filing his notices of appeal under s. 61 of the Act.

- These refusals include four counts from 31 January 2019 to February2020, by his silence, repeatedly preventing Z. Simon from filing his applications for

leave to appeal under ss. 19 (2)(a) and 32 (1)(a) of the Rules of the Supreme Court of Canada.

- He has successfully obstructed/defeated the course of justice on 2019-12-18 by refusing to file Z. Simon’s

submission required by the Honourable Mr. Justice Rowe.

- Sweeping or misleading allegations received from various counsel to AGC:

- AGC’s Response to Civil Claim with false statement, filed on June 26, 2014.

- AGC’s Response

to Notice to Admit filed on 2014-11-04.

- AGC’s Response to Civil Claim with false statement, filed on 2017-05-11.

- The 2018-07-18 order of Gleason J.A. (Docket: A-123-18) refused to settle the contents of the appeal book, prohibiting

all further steps prescribed by the Rules. She ordered the Crown to proceed by its vexatious litigant motion, not by an application.

- Another single justice of the FCA, instead of three judges, obeyed her unlawful order and

declared Z.A. Simon a vexatious litigant in his order issued on 2019-02-08.

- On the same day, an alleged 3-justice panel, without a hearing and not having the documents on file required by the Rules, while referring to 48 grounds of appeal,

dismissed Z. Simon’s appeal. [A party cannot submit documents within one day.].

- Z. Simon was not allowed to be heard. It was a violation of s. 16(1) of the Act.

- The 3-judge panel was in a hurry, occupied

with the Elson v. Canada decision in the same morning. Stratas J.A.’s Reasons for Order was entered in the J. & O. Book (Vol. 305) later than their Order. The FCA has not issued this order officially, either.

- After

several years of hard legal work and coincidence, or Providence, between 31 January 2019 and February 2020, the instant plaintiff had four different appeals ending up in the Supreme Court of Canada in the same period. Two of them appealed the decisions of

the Federal Court of Appeal (one originating in the Federal Court and another in the Tax Court of Canada), one appealing the decision of the British Columbia Court of Appeal, and one appealing that of the Alberta Court of Appeal.

- Since the Registrar

and his Registry Officer colleagues have habitually and repeatedly prevented the filing of Z.A. Simon’s Notices of Appeal under section 61 of the Supreme Court Act since 2012, he was forced to submit all of them as applications

for leave to appeal. Otherwise, the Registrar could have created a situation that any submission would have missed the prescribed deadline for service and filing, or he could have declared him vexations litigant in the SCC for duplicate submissions.

- By

prohibiting Z.A. Simon to submit his documents under s. 61, the Registrar forced him to play a kind of Russian roulette where each choice meant a bullet. When a party alleges error in the court appealed from, it is mandatory by law

to proceed automatically by appeal, not by application. “Choosing” application, a party formally admits that the lower court did not make any error in law in its decision. The SCC receives 800-1000 such applications per year. Maybe no

judge has the time to read all those submissions completely. Those parties have almost zero chance to succeed.

- During the last few years, the first application for leave to appeal was received by the Registrar of the Supreme Court of Canada on December

31, 2019. The second one was received by him in mid-March 2019.

- Ms. Proulx, an employee of the SCC Registry, made the six sets of these two documents disappear, virtually by wizardry: she refused to assign file numbers to them. Officially they have

never been stamped as “Filed.” Instead, she assigned “Internal reference numbers” to both sets of submissions that is a tort not allowed by the Rules.

- The Rules of the Supreme Court of Canada does not allow

such trickery that constitutes a contravention of s. 139 (2) of the Criminal Code (obstructing justice).

- In short, these four appeal documents together were ready for the disposal of the Supreme Court of Canada, but the Registry

prevented the Court to see and read the four submissions together. Such cavalier inquisitorial practices in Ottawa are not saved by legislation or common law. It is a systemic intentional procedural tort of the Crown,by the high-handed actions and omissions

of its servants including Ms. Proulx.

- By stopping our appeals in the SCC by contravention of s. 139 (2) of the Code, SCC Registry Officer Proulx has stolen the last opportunity of the Government of Canada in early 2019 to

recover moneys from the tortfeasors of the Government of British Columbia, or shift part of the financial responsibility to that Province.

- In mid-2019, the plaintiff tried to break the silence of the Registry’s officers.

- His motion

was received by the Honourable Justice Rowe who, on November 20, 2019, allowed to file a motion for extension of time. He did not specify what date shall be shown on the ‘proper’ applications for leave to appeal while the two proper and compliant

applications were already laying in the Registry for over six months.

- T. Proulx, R. Bilodeau, or another SCC Registry Officer misinformed Mr. Justice Rowe, alleging that our first two submissions were out of time and improper.

- The first one, the BCCA order, had a 14 December 2018 stamp of preliminary entry and an 18 December 2018 final date stamp for its entry. Thus, Z.A. Simon could not have received that BCCA order before December 18, 2018. The SCC Registry’s letter

of 8 February 2019 admitted receipt of six sets of our Application for Leave.

- Section 80 of the Rules of the Supreme Court of Canada states that judgements take effect when deposited with the Registrar:

in our case on 14 or 18 December 2018.

- The BCCA Order was deposited in the Vancouver Registry only on December 18, 2018. Tina Proulx admitted our application for leave to appeal on 2019-02-08.

- 52 days elapsed between them, without

the 12-day winter recess in Rule 5.1.

- Ss. 58(1)(a) of the Supreme Court Act allows 60 days from a judgment to serve and file an application for leave to appeal. The Nov 22 date of Reasons did not

count.

- Ms. Proulx misinformed the SCC and, without authority and against the Code, demanded on 2019-03-27 a motion for extension of time. Z. Simon ignored it.

- As for submission #2, appealing the FCA order originating in the Federal

Court, Ms. Proulx refused its filing and required an Amended Notice on 2019-05-22.

- The “irregularity” was the uncertainty that Z. Simon’s appeal did not specify the file number of the 2019-02-08 FCA Order of Stratas J.A. that confirmed

the 2018-10-30 Direction of Zinn J. of the Federal Court to its Registry not to file Z. Simon’s application for leave and judicial review of a single IAD decision of Mr. Tucci (File No.: VB6-01190, Client ID: 81808360, UCI: 58083938, Application: F000355596).

- The said FC Direction of Zinn J. contained no Court file number on it, and the decision of Stratas J.A. did not assign a separate file number for its appeal, either.

- Parties cannot assign arbitrary file numbers to decisions of courts or judges

and cannot “correct” or “improve” any “irregular” decision. See Proulx’ letter 2019-05-22.

- Tina Proulx should have sent out a request for direction to a justice of SCC.

- The SCC Registry’s 26

October 2020 letter admitted that Z. Simon submitted the documents “in those matters on December 18, 2019” but they refused to file them.

- The Registrar did not specify a section of a law or the Rules for his refusal.

- In

any case, the Honourable Mr. Justice Rowe could not read my submissions.

- The Registry informed Z. Simon that the SCC was expected to deliver a decision in his other cases on December 17, 2020. So far, he has not received anything.

- Z. Simon

sent a list of questions to the SCC Registrar, the Minister of Finance and the AGC under s. 7 of the Access to Information Act but none of them responded.

- If Z.A. Simon needs to live in China, he could not get meaningful

and efficient access to a treatment in a hospital, including an intensive care unit or surgery, due to the language barrier. His Cantonese knowledge is under a bare minimum. Employees of China’s hospitals cannot communicate with him in English (Hungarian

or Spanish).

- He is concerned that, in case of his death, the Crown would not pay his wife, ZuanHao ZHONG, the lawfully prescribed amount of survivor’s pension benefits on the alleged accusation that their marriage has not been genuine. He is

not accusing or attacking the Crown for a possible future hypothetical administrative decision. Rather, having lost his trust in the Crown, he is seeking a declaration of this Court regarding the nature, status, or validity of their marriage. Is their marriage

void or voidable?

- Due to the unending torts committed by the officers of the courts and the Crown, Z. Simon is no longer as healthy as 14 years ago. Now he has high blood pressure and irregular heartbeat, between 70 and 170 per minute. He needs to

take 3 drugs. He often has nightmares or bad dreams about lists of case law or angry judges.

- After 14 years of legal work and sleeplessness he lost his pride as a Canadian.

- The family is forced to maintain separate households: in Alberta

and China.

- Most Chinese immigrants are hard workers. Since 2007, Canada has lost two of them. Without the torts, the family would likely have a house paid by three earnings.🙂🙂🙂🙂🙂🙂🙂🙂PART II - A statement of the points in issue

- The plaintiffs respectfully submit that the proposed trial will involve the following issues, respectfully requesting the Court to certify those questions of law:

- (a) Does the Registrar of the Supreme Court of Canada have jurisdiction to

declare an unambiguous provision, section. 61. of the Supreme Court of Canada Act impracticable or invalid without an Order of that Court?

- (b) Or does the Registrar of the Supreme Court of Canada have jurisdiction under the

Supreme Court of Canada Act to prohibit parties from filing appeals automatically, without the application stage, as prescribed by s. 61. of that Act,if they clearly allege error(s) in law in the judgement of the court appealed

from?

- Then, if so, what is the legislative basis for the Registrar’s prohibition(s) or refusal(s) issued in a brief personal letter that is not appealable, instead of an order?

- Are registry officers of the SCC above the law, including

the Criminal Code?

- Is s. 52 of the Supreme Court Act (“The Court shall have and exercise exclusive ultimate appellate civil and criminal jurisdiction” in Canada) impracticable because such ultimate

jurisdiction can be exercised by the SCC Registrar in his personal capacity through his personal letters that cannot be appealed under s. 78 of the Act?

- May the SCC Registrar adopt procedures inconsistent with the Act

or Rules?

- Pursuant to ss. 8 (2) of the (SCC) Rules, may the SCC Registrar refuse to file a document that complies with these Rules and has been served according to them?

- If the SCC Registrar does

not issue an Order and ss. 8 (2) of the Rules does not apply, is his opinion issued in the form of his personal letter binding for a party?

- Does ss. 19 (2)(a) of the (SCC) Rules allow the SCC Registrar

to procrastinate and completely ignore a properly filed and served document for months or years?

- If the SCC Registry properly receives copies of served document and a Registry Officer assigns an internal reference number to it, has a file been “opened

by the Court” under ss. 27 (1) of the Rules of the Supreme Court of Canada?

- Does ss. 32(1)(a) of the (SCC) Rules allow the Registrar to do nothing but procrastinate? (He has failed to submit

our first two applications to SCC in 2019).

- Is it acceptable behaviour from counsel, officers of the Court, to habitually submit sweeping or untrue allegations to judges, constituting grave abuses of process?

- Are the Charter and

the rule of law still in force in Canada, with the principle of stare decisis respecting the decisions of the Supreme Court of Canada?

- If the word abeyance is missing in the legislation, may it make the related laws, s.

3 of the FC Act and s. 3 of its Rules, impracticable? (Faster, better administration).

- If subsection 40 (1) of the Federal Courts Act, RSC 1985, c F-7 prescribes

that the Federal Court of Appeal may issue a vexatious litigant declaration on application (to be heard by three justices), may that Court issue such valid declaration on motion as well, heard and decided only by a single justice, contrary

to the national standards?

- If so, is such vexatious litigant declaration made by a single justice valid in law if the Court did not have a consent letter signed by the Attorney General of Canada?

- Is ss. 6 (3) or 1.1

(1) of the Federal Courts Rules inconsistent with ss. 27(2) of the Federal Courts Act, and its rule about the exclusion of Christmas recess from the reckoning of time is impracticable and invalid, based on

argumentum ex silentio?

- Two judges, Rennie J.A., and Evans J.A made opposite decisions in this issue:

- Rennie J.A. on 1 March 2017 (Docket 17-A-3) wrote, “The applicants do not advance any explanation for the failure to file

within 30 days prescribed by section 27(2) of the Federal Courts Act, R.S.C.1985, c. F-7. The sole explanation offered, that they sought to shelter under the Christmas recess under Rule 6(3), does not assist, as that rule does not affect time periods

set by statute…” (He dismissed our motion.).

- The Honourable Justice Evans J.A. (FCA) wrote the opposite on 2013-03-22.

- The first approach ignores section 12 of the Interpretation Act and s. 12

of the Charter. The second one respects them. The first one fails to reconstruct the legislative intent: The Rules Committee has found a gap in the Act and inserted a rule for it. Nothing in the Act or Rules states that the days

of Christmas recess must be included in the reckoning, or that the reckoning of days must be continuous. There is no incon-sistency between the Act and the Rules. Argument of silence is a misleading concept.

- Rennie J.A.

overlooked the legislative intent in s. 46(2) of the FC Act in a no provision situation. He cannot show that the order of Evans J.A. was manifestly wrong.

- S. 5.1 of the Rules of the Supreme Court

of Canada states that the time period from December 23 to January 3 must be excluded from the computation of days.

- Nothing in s. 58 of the Supreme Court Act indicates that it invalidates Rule 5.1. Further,

section 1 of the Rules implies that the Registry is obliged to observe every rule, “Except as otherwise provided by the Act or any other Act of Parliament, these rules apply to all proceedings in the Court.” The Interpretation

Act is “another Act of Parliament.” Its section 12 prescribes, “Every enactment is deemed remedial…”

- Is it procedural fairness if Canada’s Court registries send the decisions of judges with

delays of several days or weeks to a party, and extension of time is denied?

- Is it procedural fairness if an increasing number of judges issue only reasons?

- Since reasons without orders are not judgments but often explanations or lists of

possible solutions, and time never starts to run, can hundreds of parties file a class action against the Crown or registries for their losses resulting from such torts?

- If the IAD policy expressed by Kashi Mattu in Chen sharply contradicts

the FCA decision in Kaloti v. Canada regarding ss. 4(1) of the IRPR, which one is correct?

- If “criminal courts are not staffed and equipped to cope with such types of determinations” for civil remedies,

and “civil remedies should await action in a civil court”, and parties do not wish to bring criminal proceedings against ministers, are federal ministers free to commit “quasi-criminal” torts that do not belong to any Court?

- The

Justice Laws Website shows a New Layout for Legislation, “as part of ongoing efforts to improve access to justice for Canadians” effective January 2016. It illegally modifies the Charter’s meaning by shifting its

(informative) marginal notes into (mandatory) headings, without Parliament’s approval. Such “improvement” is placing criminals and suspects into a protected box, granting them many privileges but innocent victims of Crown torts are

not protected anymore directly by ss. 11(a), (b) and (g) of the Charter (innocent until proven guilty principle, etc.), only indirectly by its ss. 15 (1). Other laws have a LAYOUT paragraph explaining the

“for convenience of reference only,” revealing the true unlawful purpose of the Charter’s new layout.🙂🙂🙂🙂🙂🙂🙂🙂🙂🙂🙂🙂🙂🙂🙂🙂🙂🙂🙂🙂🙂🙂🙂🙂🙂🙂🙂PART III - A concise statement of submissions

- The

Federal Court has jurisdiction in these issues, and the ITO test is met.

- Referring to the Government of British Columbia under the “Facts” does not mean that the plaintiffs have any claim here against BC in the federal court system.

- Dozens of civil servants, mainly officers of the Court under the AGC’s control, repeatedly and habitually, in bad faith, breached the principles of procedural fairness.

- Even if a judge declares that s. 8 of the Charter

is invalid and the Crown may seize non-existing debts without any court order, the issue of s. 61 of the Supreme Court Act remains unresolved: under it, Z. Simon always had a right to a direct, automatic appeal to the nine justices,

but Mr. Bilodeau has always contravened it and 139 (2) of the Code. The outcome of the s. 8 Charter issue, if decided by a judge, has no bearing on the inapplicability of s. 61. This action

is brought for the legitimate purpose of seeking the vindication of legal rights of the plaintiffs. Their primary aim has been family reunification. The ultimate goal is to protect the SCC’s full powers.

- His previous statement of claim, para.

16 on page 5 sought a decision or declaration regarding the possibility to grant “conditional permanent residence” by “conditional measure” for his wife. There is no judgment by www.canlii.org about such solution or wording associated

with his name so it was not an abuse of process.

- The plaintiffs plead fraudulent conversion, fraudulent misrepresentation and unjust enrichment of the Crown, a corresponding deprivation of the plaintiff; and an absence of

juristic reason for the enrichment (see Garland, 2004 SCC 25, para. 30).

- Subsection 380. (1) (a) of the Criminal Code states, “Every one who, by deceit, falsehood or other fraudulent means, whether or not it

is a false pretence within the meaning of this Act, defrauds the public or any person, whether ascertained or not, of any property, money or valuable security or any service, (a) is guilty…”

- The plaintiffs respectfully submit that this

applies for the Crown: two federal ministries (CIC and MNR/RCA) with the approval or encouragement of AGC in 2006-2020 kept defrauding the public by running a money extortion/laundering scheme.

- They submit that the AGCs knowingly neglected to review

or terminate the money laundering activities of FINTRAC, and report it to the PMO or Parliament.

- Mr. Bilodeau’s booklet entitled Representing Yourself in the Supreme Court of Canada, Vol. I tortiously omits section 61.

of the Supreme Court Act how to proceed.

- The Attorneys General have failed to correct such misleading tort situations.

- The plaintiffs claim that the Attorneys General have been vicariously liable for the harmful acts and

omissions of the Crown’s servants. They plead lost opportunities.

- The Anns/Kamloops test is met since the Crown (IP 2) alleges a contract between a minister and the family class sponsors. Such relationship of proximity

imposes an obligation to take reasonable care to prevent foreseeable harm to them.

- Para. [8] of Busnex Business Exchange, 1999 BCCA 78 states: “A liquidated demand is in the nature of a debt, i.e., a specific sum of

money. Its amount must either be already ascertained or capable of being ascertained as a mere matter of arithmetic. If the ascertainment of the sum of money, … requires investigation, beyond mere calculation, then the sum is not a debt or liquidated

demand but constitutes “damages”.

- Canada has stubbornly declined any mitigation of irreparable damages caused for the plaintiffs. As a policy, its consulates refuse to entertain visitors visa applications of persons whose

immigration request was denied, whether lawfully or unlawfully.

- The AGCs and their counsels, ministers of immigration and national revenue, two IAD panels, Zinn J. and Mr. Stratas J.A., were all representing Canada as a state.

- After two refusals

(2007 and 2016) of our family reunification efforts it seems clear that the powerful ones are adamant in our unlawful and forced separation forever.

- That may bring sadistic pleasure for one or more “honourable tortfeasor.” Such pleasures

of mental torture and abuse of Charter rights may come with high price tags.

- One of the remedies being sought by plaintiffs is an equitable one in our case.

- The plaintiffs claim damages for mental distress and humiliation

(Fidler 2006).

- The plaintiffs claim repeated denials of their right to a fair hearing since 2011.

- This case is like a race between two sports teams. One is a political power pyramid relying on a host of oppressed or corrupted public servants

that act by fear, to please the ones on the top. The second team uses law, sound reasoning and 150+ years of Canadian court experience, led by the nine justices of the Supreme Court of Canada. The power team hopes that they are the winners of the cup, and

the SCC justices will go down the drain or become a “paper tiger” soon. Such issue is novel in law or history.

- In 2016, Prothonotary Aylen was clearly wrong in assuming that addressing the controversies regarding the CIC forms named IMM

1344 (08-2014) E and its updated version IMM 1344 (03-2016) E would be an abuse of process or res judicata. If our pleadings before Madam Justice Donegan in 2015 BCSC 924 was silent about those unconstitutional forms, that must be read in tandem with

CIC Guide 3900 – Sponsorship of a spouse…, how could the pleading of that tort be abuse of process?

- I.e., the form IMM 1344 (03-2016) was issued only in 2016 so a Court could not have addressed the question

of its unconstitutionality in 2015.

- Question 9 on page 2 of 7 of the said form (entitled Application to sponsor, sponsorship agreement and undertaking) asks: “Have persons you previously sponsored or their family members received social

assistance during the validity of the undertaking?” The related “Sponsor Eligibility Assessment” in Guide 3900 goes: “If you answer “Yes” to any question between 5 and 15 You are not eligible to be a sponsor. You

should not submit an application”.

- This tort is damaging Canada’s immigration by a cruel reduction of qualified sponsons and contravenes ss. 3 (1) (d) of IRPA and the IP 2 because ss. 135

(b) (ii) of the IRP Regulations defines the end of the default of a sponsorship undertaking when “the sponsor ceases to be in breach of the obligation set out in the undertaking”.

- Limitation law terminates a breach or default

if the Crown is silent or inactive for six years, without a self-help action, as in our case (see Markevich, 2003 SCC 9).

- So far, no Canadian court has addressed this tort that unlawfully disqualifies and prevents the immigration of ideal

candidates, sponsored persons in the family class. Reading these two CIC documents together, eligible sponsors under the IRPA and IRPR are prohibited from sponsoring their spouses, children, or parents. Instead, Canada is filling up their

places by dubious applicants with criminal background.

- The plaintiff alleges intentional breaches of statutes amounting to misfeasance of office since it is established that the officials concerned deliberately acted unlawfully with knowledge

that their actions would harm the plaintiff: Odhavji, 2003.

- The plaintiff claims that the AGCs had vicarious liability on the part of the Crown for the Commissioner of Revenue of the Canada Revenue Agency, the Deputy Minister of

CIC, when supervising the Crown’s lawyers compiling the tortious MOU policy, also the registry officers of the SCC Registry, as identifiable Crown servants.

- In 2006, the AGC knew that the federal Crown’s lawyers denied responsibility

regarding the possible illegality of the MOU: “This MOU… is not intended to be legally binding or enforceable before the Courts.” In other words: It is unlawful, and civil servants must prevent persons from taking it or

issues related to it to any Court.

- In her response to Notice to admit, in File No. 4756 (Golden, 2014), the AGC “says that ‘IP 2 Processing Applications to Sponsor Members of the Family Class’ provides policy and procedural

guidance for processing sponsorship applications.”

- The repeated false statements of CIC and CRA have been made knowingly or in circumstances amounting to culpable conduct. The latter is defined in s. 163.2(1) of the ITA

as conduct, whether an act or a failure to act, that (a) is tantamount to intentional conduct, (b) shows an indifference as to whether this Act is complied with; or (c) shows a wilful, reckless, or wanton disregard of the law. These all apply here.

- “[W]ilful,

reckless or wanton disregard of the law” refers to concepts well known to the law, commonly encountered as degrees of mens rea in criminal law: see, e.g., K. Roach, Criminal Law (5th ed. 2012), at pp. 180-84 and 191-92. The use of such

terms evinces a clear intention that “culpable conduct.” See [57] of Guindon.

- If this definition of false statement applies for taxpayers, it should equally apply for a Minister of National Revenue. Notices of tax assessments

are statements.

- If there is a credit amount payable to the taxpayer as the subtotal but in the last line it disappears without reference to a section of a law, the CRA statement is false.

- Question to be certified:

If a taxpayer’s wilful, reckless, or wanton disregard of the law is punishable, would the same attitude of a few federal ministers acceptable?

- No reasonable judge* abroad or in the SCC would conclude that three federal ministers (Citizenship

and Immigration, National Revenue, and Justice) innocently overlooked a nationwide money extortion scheme since 2006 by negligence, or a grassroot movement of their public servants that had revolted from the rule of law. Rather, it was a concocted, concerted

action of three ministers and their successors inherited the instituted Crown tort; [Note for the *: every judge is reasonable.]

- The idea was brilliant, whether or not the product of the Nation’s Genius: Seize monies of innocent citizens by

CRA’s force without any Court and send those monies to the provinces as gifts from the Federal Government, with no colour of law.

- The required factors – blameworthy conduct, prevalence of conduct necessitating deterrence, lack of empathy

for the victims and lack concern for the consequences to the victims (the re-victimized sponsors) – are present here.

- Cases of money extorted by an abuse of legal proceeding are few: Windsor.

- In Khadr v. Canada,

2014 FC 1001 (CanLII), Mr. Khadr sought $20,000,000 in damages, and received $10.5 millions from PM Trudeau. The detention and torture of A. Almalki, A. Elmaati and M. Nureddin were similar to those of Syrian Canadian Maher Arar. They received $10 to $10.5

millions each. The law does not specifically say that only Moslems may get such monies while other Canadians cannot.

- Similarly, Z.A. Simon and his family are suing Canada for compensatory damages for two conspiracies (SCC Registy;

CIC+CRA) and misfeasance in public office; Charter damages pursuant to s 24 (1) for breaches of ss. 7, 8, 12, 15 (1), 36 (1)(c) and 52

(1) of the Charter and ss 139 (2) of the Criminal Code; punitive and aggravated damages; and special damages, also claiming lost future incomes.

- In Henry v. British Columbia, the Honourable Chief Justice

Hinkson granted Mr. Henry a total of $8,086,691.80 in three types of damages. Considering that inmates of Canadian prisons get the best quality food and good living conditions, a price tag of $10 million is a bargain for Canada. The powers of the Supreme Court

of Canada and the rule of law do not have a price tag. After all, Z.A. Simon did a remarkable work from 2007 to 2021 that belonged to the job descriptions of the Attorneys General.

- Canada wasted 400 million dollars on Phoenix Pay System without a

solution.

- 79 Canadian cases refer to the emotional trauma resulting from a snail in a bottle of ginger beer but not a single case law deals with the protection of the rule of law or SCC’s powers, or access to justice through s. 61

of the Supreme Court Act.

- Re-victimized sponsors like Z. Simon get zero trial time in any Court while in Morrison-Knudsen Co., Inc. v. British Columbia Hydro the trial took 396 Court days.

- The trial took 16 months in R.

v. Trudel, 2007 CanLII 413 (ON SC).

- Just after the 1995 Quebec referendum I made a research calculating the ratios of Yes and No votes by ridings. I suggested to 60 powerful Canadians by maps that using 67%, a thin corridor along the US border

would still connect the rest of Canada with the Maritimes if Quebec would separate. It has solved Quebec’s issue for good.

- Of course, if the rule of law is history, the Federal Court is free to impose a life sentence on Z.A. Simon on the basis

that he is Canada’s most dangerous man.

- Ss. 36. (1)(c) of the Charter grants “essential public services of reasonable quality to all Canadians.” Assigning sufficient man hours to each decision-maker of the

Federal Court in novel and complex cases of great societal importance – virtually at no costs to the Government – falls under such Charter guarantee. The courts shall maintain at least the illusion or the reputation of the good administration

of justice.

- Between 2012 and 2020, the Government of Canada and two provinces have repeatedly denied Z.A. Simon good quality services in the courts and their registries.

- The registries blocked ca. 40% of his submissions from the courts. None

of the courts have delivered a final judgment (jugement définitif) that determined any substantive right between he and the Crown as defined in s. 2 (1) of the Supreme Court Act,

RSC 1985, c S-26, also in ss. 2 (1) and 27 (4) of the Federal Courts Act.

- Thus, the courts, due to the Crown’s stonewalling and denial to disclose facts, delivered their decisions in a factual vacuum,

based on false allegations or perjury.

- Between 2012 and 2020, practically all of court cases involving Z.A. Simon involved major procedural unfairness or lack of jurisdiction influencing the outcome.

- Three justices or courts of BC stated

in 2015-2019 that the same plaintiff had pleaded 20 to 60 possible causes of action. The merits of these 60 causes of action and 60 “clearly arguable questions of law” have not been addressed by any court.

- In 2021, the instant plaintiff

submits ca. 70 causes of action against the Crown.

- The plaintiff has pointed out in the past that if the sponsors give a 100% guarantee that the sponsored persons would not apply for social assistance for 10 years it could be achieved only

by their forcible confinement for a decade, a serious offence under s. 279 of the Criminal Code. The cornerstone of the Sponsorship Agreements is a condition to commit an indictable offence; it renders them illegal or void

ab initio.

- The courts, in two Bilson v. Kokotow cases, stated that parties alien to a contract cannot claim damages under it. The Crown has not signed our undertaking forms.

- While a few Canadian judges, including Madam Justice

Donegan, allege that a breach of statute is a tort not known at law, the plaintiff’s version of the Criminal Code states, “Disobeying a statute 126 (1) Every person who, without lawful excuse, contravenes an Act

of Parliament by intentionally doing anything that it forbids or by intentionally omitting to do anything that it requires to be done is, … guilty of (a) an indictable offence…” Contravention is breach, breaking

the law, in our vernacular;

- The plaintiffs claim commission of an “abuse of power equivalent to fraud” and “resulting in a flagrant injustice”: Landreville v. Boucherville (1977, SCC).

- They

claim recovery of moneys paid under a transaction prohibited by statute.

- The plaintiffs sue Canada for general damages, damages in tort, or damages in contract if the Crown can demonstrate that a contract existed [see BG

Checo, 1993].

- The plaintiff(s) claim vicarious liability of the Attorneys General (AGC) in tort in 1998-2020 on the part of the Crown for several identifiable Crown servants.

- The plaintiff(s) claim unlawful interference

with economic relations, which is also referred to as intentional interference with economic relations. They plead the elements of such torts as Cromwell J. stated them in A.I. Enterprises, 2014 SCC 12.

- Accordingly, the third

party was the Government of British Columbia. Namely, CIC, RCA and AGC, since 2006, mislead, allowed and incited BC to pay social benefits unnecessarily to a person (Ms. Reyes) for 5 years, as a secure investment; giving BC a “blank cheque” allegedly

signed by Z. Simon, promising to that Province that it can get a guaranteed windfall from CRA at any time after the limitation period.

- CRA allowed a ministry of BC to charge ca. 6.37 per annum compound interest on Z.A. Simon non-existing

debt, well above the lawful 5% maximum annual rate.

- The plaintiffs plead fraud. The test for fraud, by Dickson, J., is satisfied by the Crown’s dishonesty and a family’s deprivation, deprivation of re-victimized

sponsors.

- The plaintiffs claim abuse of power or public office by dozens of Canadian civil servants (based on Klar, Linden, Cherniak and Kryworuk’s Remedies in Tort). The plaintiffs can establish on a balance of probabilities

that (1) The Crown Defendants knew that they did not have the power to do what they intended to do, but nevertheless carried out their acts, notwithstanding the detrimental effect upon the Plaintiffs; or/and (2) The Defendant’s actions were carried out

with the specific intent and purpose to punish the plaintiffs and the class of re-victimized sponsors.

- “Where fraud, misrepresentation or breach of trust is alleged, the pleading shall contain full particulars, but

malice, intent or knowledge may be alleged as a fact without pleading the circumstances…” The plaintiffs allege all these elements.

- The plaintiffs plead bad faith, improper motive, malice, or/and deliberate

conduct calculated to interfere with economic relations to their detriment.

- Charter rights of “persons cannot be held in abeyance while the system works to respond to this new framework.” See R. v. Jordan, 2016 SCC

27 (CanLII), para. 98.

- Z. Simon is suing Canada for loss of reputation and defamation by its counsels acting in concert since 2012, by pleading scurrilous and unsubstantiated accusations against him: fanciful, vexatious, rambling,

inability of writing properly. See Hill, 1995.

- The three-pronged test as set out in Grant v. Torstar, para.[28] is satisfied.

- From Ms. Bridges (2012) to Mr. Sinnott (2020), several counsel to AGC kept falsely alleging in

the courts that Z. Simon’s submissions were frivolous, vexatious, or an abuse of process, and did not contain any true or proper facts. They depicted him as a mere unreasonable busybody debtor that kept suing the Crown with no reason.

- Counsel

kept repeating the defamatory words knowing they were false or with careless disregard for their truth, knowing that once the whole world could read them.

- Those accusations have misled many judges and ended up on www.canlii.org

so the whole world got the impression that Z.A. Simon was a No. 1 vexatious idiot.

- Worse, Z. Simon was consistently fighting for the restauration of the rule of law in Canada and the powers of its Supreme Court. Counsel to AGC, hiding behind Her Majesty

the Queen’s name and referring to Z.A. Simon’s name as the possible worst vexatious litigant in Canada, helped the Crown to punish a wide class of victims with extreme cruelty, contrary to the Geneva Conventions Act and the Charter.

- The plaintiffs are not seeking criminal punishment or consequences for any of the public servants involved by quasi-criminal acts or omissions; rather civil remedies.

- London Insurance [1963] SCR 207 refers to case law about “the

commission of a criminal or quasi-criminal offence in civil cases as it has been accepted in” SCC.

- The plaintiff pleads for punitive and aggravated damages based on deterrent effect.RCA’s, CIC’s, and AGC’s

complicity from 2006 to 2020 has been pleaded.

- The plaintiffs have no obligation to provide, on 30 pages, the full list of employees of three ministries that have, under pressure, participated in these torts since 2006. In Just,1989 (SCC),

Mr. Just succeeded without giving the tortfeasors’ names.

- Similarly, it is sufficient to point out, as a smoking gun, that www.canlii.org does not list a single SCC appeal under s. 61 of

the Supreme Court Act as of right.

- Access to the courts for vindication of legal right is part of the rule of law.

- In Kaloti v. Canada,2000 CanLII 17123 (FCA), the Court stated: [5] Relying on the decision of this Court

in O’Brien v. Canada (Attorney General), Dubé J. expressed himself as follows: [8] …The only “circumstance” in proceedings under subsection 4(3) of the Regulations is the intent of the sponsored spouse at the

time of the marriage. That intention is fixed in time and cannot be changed.

- On the other hand, the policy of the IRB-IAD Panel(s) it totally different:

- IAD Member Mattu’s wish list suggests many factors. In Chen, she found:

“the existence of a genuine marriage is a question of fact and includes a mix of the past, current and future state of affairs in the relationship.” But future is speculative only.

- As confirmed by the Supreme Court of Canada in F.H.

v. McDougall [46], the evidence must always be clear, convincing and cogent in order to satisfy the balance of probabilities’ test. The two IAD panels did not show any evidence against plaintiffs.

- Visa officers cannot establish incompatibility

of spouses because they “did not hold the candle during their nuptials”, so to speak. It is patently unreasonable to demand proof beyond reasonable doubt for lack of good faith. The Crown should prove the existence of bad faith.

It is impossible to prove the non-existence of something (say, UFO’s or angels). Alleged incompatibility is a s. 15 (1) Charter infringement.

- Most of Canada’s tribunals could not prove that their spouses

did not marry them for their status or salary. Canada shall not use stricter standards for immigrants.

- As the child of Italian immigrants, the story of Mr. Lametti’s parents is one of generational sacrifice: they left their home and came

to Canada so that their children could have a better life than they did. This admits that they immigrated to enjoy the privileges in Canada, but he has no evidence that Z. Zhong married Z. Simon for that.

- It was perplexing to read, “…the

motion filed on September 8, 2020, cannot be accepted for filing in files 38747, FD-02394 and FD-02480; however, the motion has been accepted for filing in files 39294 and 39295.” None of the SCC Rules allow an employee of the Registry to judge

if a submission obeyed or not an order of a justice. Only the judge involved has authority to do that, and Z. Simon complied with his order.

- The decision of the SCC Registry to “evaporate” our submissions in files 38747, FD-02394 and FD-02480

has been made without jurisdiction. It infringed on our ss. 12, 24 (1) and 52 (1) Charter rights and ss. 139 (2) of the Criminal Code.

- In Honey Fashions,

2018, Justice Zinn wrote: “It points to Dunsmuir v New Brunswick, 2008 SCC …, wherein the Supreme Court of Canada at para 55 stated that questions of law of central importance to the legal system and outside the specialized area of expertise

of the administrative decision-maker attract a correctness standard.

- The review of refusals of visa officers (in 2007 and 2016) to issue permanent resident visas for Mr. Zhong and Mr. Ye should have attracted a correctness standard.

- IRB-IAD

failed to apply the correctness standard in both appeals (2009, 2018).

- In June 2006, Counsel to the Minister of CIC knowingly counseled, induced, and aided CIC to indirectly misrepresent or withhold material facts relating to a relevant matter –

sponsorship debt – that induced errors in the administration of the IRPA, pursuant to its sections 126 and 131. Also, the decision of the SCC in Canada (Attorney General) v. Mavi, 2011 SCC 30 (CanLII),

[2011] 2 SCR 504 is a material fact, stating that there is no debt without a ministerial certificate in the Federal Court.

- Since 2006, by MOU and IP 2, ministers of citizenship and immigration have knowingly misrepresented the IRPA

and the relevant facts, contravening its s. 127, that induced errors in its administration with intent to deter immigration to Canada.

- Since ca. 2015, ministers of citizenship and immigration have knowingly mis-represented the IRPA

by issuing Guide 3900 with Form IMM 1344 containing a tort at Question 9 on page 2 of 7, violating its s. 127, inducing errors in its administration with intent to deter immigration to Canada and perhaps to please white supremacists.

- Since 2006, each AGC has been guilty of an offence or criminal negligence for failing to maintain a file in the Federal Court that listed the registered ministerial certificates of debt, required by s. 146 (2) of the IRPA, so

obstructed or impeded every visa officer in the performance of their duties, pursuant to ss. 129 (1) (d) of the IRPA.

- Since 2006, the AGCs knowingly counseled, induced, aided, or abetted two ministries (CRA and CIC) to mislead

civil servants, the provinces, and the sponsors.

- The sponsors’ vulnerability is a “golden thread” uniting such causes of action as breach of fiduciary duty, undue influence, unconscionability and misrepresentation.

- If the Crown has chosen to contravene 60-80 paragraphs of the laws of Canada and BC since 2006, it should pay for the resulting damages to the key victims.

- The Attorneys General, after more than a dozen court cases (in BC, Alberta and Ottawa)

spanning 14 years (2007-2021), know more material facts about Z.A. Simon, his family members and the torts of the Crown than the plaintiff himself.

- AGC and his counsel can get PDF files of our four (aborted) appeals to the SCC Registry if they wish,

to get more detailed information, documents, facts and law.

- The high number of motions in Z. Simon’s past cases is a good indicator for the high number of irregularities and unlawful acts or omissions on behalf of the registry officers and counsel:

parties need to defend themselves by the fresh step rule.

- The Court of Queen’s Bench for Alberta declared Z.A. Simon a vexatious litigant in that Court despite that he has never been heard there even once in his life.

- If our

courts are too busy, without enough time to apply the “plain and obvious test”, they would be comparable to an army of soldiers too busy with their own issues and housekeeping, not having time to defend the country from an attack of the enemy.

- Mr. Bilodeau’s and Ms. Proulx’s Stalinist salami tactics in silencing our six applications needs some attention. They isolate the SCC hermetically from the rest of Canada, usurping its powers, like cutting the wires of a fire alarm in a great

building.

- By allowing or coercing the officers of the SCC Registry to sabotage s. 61. of the Act, unlawfully prohibiting them to file those or proceed with the four appeals (as of right) the AGC implicitly admitted that he

was bound to lose all of them in the SCC.

- Attorneys General waste large amounts of money for defending unlawful Crown policies. If it is beyond doubt that any minister may seize taxpayers’ credit monies without a ministerial certificate or garnishment

order issued by a Court, and without any provision in the legislation – as in Z. Simon’s case - this is a unique opportunity for AGC to ask the SCC to turn that policy into case law. Thus, ministers would get a free hand to seize such monies in

the future, without any court order.

- If, say, 10% of Canada’s judges disobey the legislation, Parliament’s will, and the rule of stare decisis, the governments can utilize them as rubber-stamping officials, gradually terminating

the jobs of the remaining 90%. They may succeed for a while, but ministers cannot read the mind of every judge. A single justice who respects the rule of law may ruin such dream of a dictatorship, see R. v. Duffy, 2016, para. [1239].

- If ministers

nationwide can shift powers from any Court to officers of a Court unlawfully, the Courts can shift awards and monies for damages to persons and public officials that have obeyed the laws of Canada, the Constitution, and the orders of SCC.🙂🙂🙂🙂🙂🙂🙂🙂🙂🙂

PART IV - A concise statement of the order sought, including concerning costs

- The plaintiffs allege two conspiracies and seek special damages, as in [28] of Khadr v. Canada, 2014 FC 1001, also exemplary,

punitive and aggravated damages.

- Also, damages arising from breach of duty of care, breach of fiduciary duty and confidence, fraudulent breach of trust, based on vicarious liability, the Crown acting in a high-handed, outrageous, harsh, and

oppressive manner since 2011.

- The plaintiffs seek orders declaratory of the rights of the parties stating:

- (a) That the plaintiffs’ instant submission has substance, it is not obviously unsustainable and not without

arguable merit, with a s. 24 (1) Charter right to be heard.

- (b) That whether the tort of conspiracy can cover egregious government-to-government conduct is a matter that should be decided by a judge at trial, with the full

benefit of evidence and legal argument; it should not be dealt with on a motion.

- (c) That clandestine deceit, unjust enrichment, breach of fiduciary duty, or the constitutional validity of legislation are developing areas of the law: it is not plain

and obvious that the plaintiff cannot succeed on these issues, see Manuge v. Canada, 2008.

- (d) That the plaintiff may succeed with his Charter claims, a developing area.

- (e) That directions issued by tribunals not to file

properly submitted documents resulting in forced separation of spouses forever constitute s. 7 Charter infringements.

- (f) That, if Z.A. Simon and his family cannot get a fair hearing or any remedy, the ideal way to proceed

is by class action with many subclasses, in the Federal Court.

- (g) That the Federal Courts Act is silent about Christmas recess and s. 6(3) of its Rules governs; also, s. 5.1 of the Rules

of the Supreme Court of Canada governs.

- (h) That Z. Simon’s instant pleadings has met the three requirements of the Canadian Council of Churches test for public interest standing; he has been separated from his wife and stepson

for 14+ years without a scintilla of law or colour of law.

- (i) That the word “default” in subsection 133 (g)(i) of the IRPR is an unlawful duplicate of ss. 133 (g)(h) of the same Regulations,

and it results in section 7 Charter infringements by ruining families since visa officers do not need to know limitation law or claims of defaults, thus section 1 of the Charter cannot save the word “default”.

- (j) That the question of a default’s end due to limitation laws is one of pure law that falls outside the expertise of the IAD or a visa officer, see Begum v Canada.

- (k) That, therefore, if visa officers overseas and the IAD cannot

make decisions of law regarding defaults and limitation law, their decisions in that regard are invalid and may constitute section 12 Charter infringements that cannot be cured by its s. 1.

- (l) That ss. 133 (1)

(g) (i) of the IRP Regulations is ultra vires the visa officers overseas when they refuse to issue landed immigrant visas if they do not or cannot obtain ministerial certificates from the Federal Court, pursuant to s. 146

of the IRPA.

- (m) That ss. 133(1)(g)(i) of the IRPR is inconsistent with ss. 3(1)(d) of IRPA and sections 7 and/or 8 of the Constitution Act, 1982

and is of no force or effect.

- (n) That the MOU between CIC and CRA, and the CIC’s IP 2 policy’s words contract are void as being contrary to s. 146(2) of the IRPA and s. 132(4)

of the IRPR.

- (o) That, in light of policies IP 2 and MOU, sponsors in the family class did not have a consensus ad idem with the Crown when they signed their sponsorship agreements and undertakings, and those agreements

signed with the sponsored persons regarding damages are void and invalid as contracts with a Minister regarding debts.

- (ö) That family class sponsors are dependent upon the Crown’s powers. The latter can

unilaterally exercise that discretion or power. The sponsors are/have been peculiarly vulnerable to or at the mercy of the Crown by the contra proferentem rule.

- (p) That a release given to a sponsored immigrant that received social benefits

who is jointly or jointly and severally liable discharges the sponsors (Shoker, 1998).

- (q) That Z. Simon’s sponsorship default took place in October 2000 in Greater Vancouver that could not create his debt, that he kept denying, due

to Her Majesty under ss. 145 (1) (a) or (b) of the IRPA, “under this Act”, that did not yet exist in 2000.

- (r) That Crown ‘debts’ owing under the ITA are not assignable to the provinces

pursuant to s. 67 of the Financial Administration Act so CRA’s transactions are illegal.

- (s) That, if the provinces and territories are obliged to grant social benefits to each qualified person, they must include sponsored

immigrants pursuant to s. 15(1) of the Charter and cannot shift such responsibility to the sponsors without a Court order.

- (t) That Ms. Zhong and her son, Jian Feng Ye, were legally entitled to land in Canada as immigrants

in 2007-2015 because Z.A. Simon did not owe the Crown any money or obligation, and the accusation of bad faith marriage appeared only in 2016.

- (u) That Ms. Reyes, who cohabited with Z. Simon for less than 6 months, did not belong to the family class

under ss. 4(3) and 6.1(2) of the Immigration Regulations, 1978 and after 2000 he was allowed by law to sponsor Ms. Zhong, his present wife.

- (ü) That if para. [21] of Vaughan v. Canada, 2000

CanLII 15069 (FC), is rightly decided, and “prothonotaries are not judges, and by virtue of sections 4 and 5 of the Federal Court Act, they are not members of either the Trial Division or the Court of Appeal”, it is a tort if prothonotaries

issue their decisions on forms with the Federal Court’s heading, so the Crown may be sued in class actions if damages arise from the tort involving innocent late filing of appeals. See Smith, 2010 or Manuge,

2010 SCC.

- (v) That prothonotaries are not tribunals and not members of the Court if it serves the Crown’s interests; otherwise, they are tribunals and members of the Court.

- (w) That AGC’s new layout effective January 2016 modifies

the legal meaning of the Charter and it is invalid without the four-line note shown under LAYOUT for other legislation and, therefore, the old layout of the Constitution Act, 1982 governs.

- (x) That Z. Simon and his wife, Z. Zhong,

often had not had an opportunity to be heard by the tribunals, since 2011, contrary to the principle of audi alteram partem.

- (y) That, considering the high number of unanswered pure serious questions of law raised, the plaintiffs have a

reasonable chance to succeed: namely, the number of the justices of the Court that respect the rule of law and stare decisis divided by the total number of justices of the Court, multiplied by 100, expressed in percentages.

- (z) That

counsels recklessly misleading the courts is a serious abuse of process, let alone their evasive answers and the failure to provide full and proper disclosure.

- The plaintiffs seek an order that Canada shall pay an extra amount of two years of their

regular salaries, as a tax-free bonus, for the following public officers for obeying the rule of law, unless they try to contravene s. 139 (2) of the Criminal Code:

- Every employee of the Calgary Registry of the Federal Court

– Federal Court of Appeal; The Justice(s) of the Federal Court involved; the Chief Justice and Deputy Chief Justice of the FC and FCA; the three or more justices of the FCA involved in case of an appeal; the nine justices of the Supreme Court of Canada;

every employee of the SCC Registry in Ottawa (except R. Bilodeau, T. Proulx, M.A. Achakji, N. Beaulieu and B. Kincaid); E. Dawson J.A., (the Estate of) C. Layden-Stevenson J.A., and R. Mainville J.A. who all ruled in the 2011 FCA 6 case; Evans and Trudel JJ.A.

(Docket: A-367-12); A. Mactavish J. (now J.A.) in Case No. 2007 FC 1155;

- Canada shall pay an amount of $2,000,000.00 to the public officials as follow:

- The Attorney General and the Deputy Attorney General of every province and territory of

Canada if their governments participate in these court cases as interveners.

- Canada shall pay the same amount to each party added as an intervener.

- Canada shall pay an amount of $1,000,000.00 to the Canadian media as follow:

- The columnists or news reporters that write an article that is published in a major* Canadian newspaper (including online) and covers at least 50% of the area of a page, with three subject matters, mentioning: (a) the impracticability of s. 61

of the Supreme Court Act due to the registry officers’ restrictions, and the lack of access of 38 million Canadians to the Supreme Court of Canada when errors in the lower courts are alleged; (b) the ongoing unlawful separation of Canadian sponsors

from their family members by the policies MOU and IP 2, and the seizure of their tax credit monies by the Crown’s contravention of s. 146 (2) of the IRPA, without a ministerial certificate of debt filed in

the Federal Court, and without a garnishing order issued by a court; and (c) the trend that officers of the courts, serving federal and provincial ministers, increasingly obstruct justice, mislead the courts and usurp their powers, gradually reducing the courts

of Canada to “paper tigers” that would eventually deal with tiny issues such as “toothpicks” or “paper clips” only;

- The asterisk (*) above refers to the top 24 Canadian newspapers listed online at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_newspapers_in_Canada_by_circulation;

- The same amount ($1 million) to be paid to the editor-in-chief and the deputy editor-in-chief of the newspaper or magazine where such published article appears.

- The same amount ($1 million) to be paid to an active or inactive politician (Member

of Parliament or Senator) or judge whose minimum half-page and at least 500 words long published article containing all the three crucial issues, (a), (b) and (c) above, appears in one of those 24 newspapers or top 10 magazines, including online.

- The

same tax-free amount ($1 million) to be paid to the host and his or her superior of a Canadian TV or radio program for a broadcasted interview about those three questions for at least 30 clear minutes with any Canadian citizen, and the latter.

- The

same amount ($1 million) to be paid to the politician or judge interviewed in such Canadian TV program that is broadcasted, dealing with those three questions for not less than 30 clear minutes (advertisements excluded). Of course, the Prime Minister of Canada

and the AGC are primary candidates for such interview.

- The previous paragraphs only refer to publications and broadcasts that are available for the wide public at least two full days before the sitting of a Court.

- The Defendant (Canada) shall

pay to the plaintiffs a total of 10 million dollars [that is much less than the total of their four claims and their four appeals silenced by the employees of the Supreme Court of Canada’s Registry since January 2019 by repeated contraventions of section

139 (2) of the Criminal Code].

- It the Court(s) grant a total under $10,000,000.00 the plaintiffs respectfully request an order to CRA or AGC to return his monies: $3,441.68 seized on 2 June 2008 and $100.43 on 4 June 2009,

both with compound interest of 5.00% per annum,

- and a compensation for his losses caused during his bankruptcy procedure from March 2013 to March 2015, including his $4,800 paid to BDO in related fees, and $2,451.67 sent to RSBC on ca. January

5, 2015, both with 5.00% compound interest.

- Plaintiffs request to certify serious questions of general importance as follow:

- (a) In an appeal pursuant to s. 63. (1) of the Immigration and Refugee Protection

Act, in relation to what period in time should an assessment of membership in the family class under subsection 4 (1) of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations be conducted by the Immigration Appeal Division?

(Are 9+ years OK?);

- (b) If limitation law terminates tax debts (as in Markevich v Canada,2003) can the same limitation law terminate a breach, default, or uncertified debt claim in cases where the Crown has been silent or inactive for six

years, without a self-help action?

- (c) Is it mandatory or discretionary for tribunals to obey s. 12 of the Charter?