|

|

|

|

|

Harper regime's pyramid scheme revealed

Canada's unsolved judicial problems

INTRODUCTION AND UPDATE: Today (January 6, 2021) I received a question online about CORRUPTION in the countries of the world. I answered

it as follow: Depends on the definition of the word "corruption". Is it corruption to contravene the laws of your country to grab more and more power for your governing party and ministries? Is it corruption to

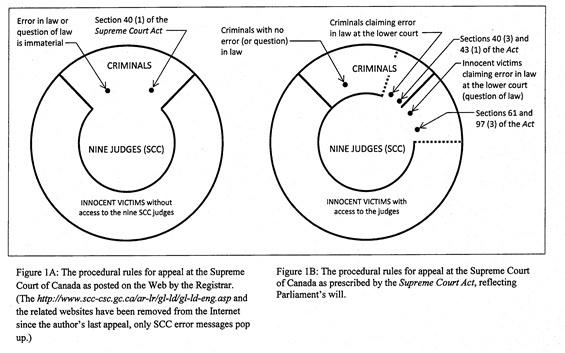

reduce the powers of the Supreme Court of Canada and shift that excess power to the federal ministers? This is what Mr. Roger Bilodeau, the previous acting Registrar of the Registry of the Supreme Court of Canada did till 2020 habitually. He kept preventing

serious issues of his country to reach the nine excellent judges of the Supreme Court of Canada, despite section 61 of the Supreme Court Act that allowed any party to be heard by the nine justices automatically and directly in cases where error in law is alleged

in the court appealed from. Mr. Bilodeau has effectively prevented the filing of two documents since January and March 2019, although he has not issued any order to me. Mr. Bilodeau, of course, is an agent of the Attorneys General of Canada. Can we call the

latter ministers “corrupt” if they keep encouraging such unconstitutional behavior and their aim is the termination of the rule of law in Canada? As you see, if two or more ministers or top public servants conspire against the rule of law and the

powers of the Supreme Court of the country, they can be called corrupt. Canada used to brag about being the most livable country of the world. Corruption is not limited to third world countries or banana republics. It is not limited to the oppression of a

country by police or machine guns. Corruption can be achieved by pressuring every employee of a ministry to tell lies and/or violate the legislation by a peaceful and friendly manner and with a smile on their face for the media. In this sense, yes, Canada

is a corrupt country. [Here ends the update.] PART I – A concise overview: The material and legal issues occupied thick volumes in the lower courts. Please refer to those submissions

if you are interested in the details. The constitutional questions below are self-explanatory. Due to the 1.5 spaced line requirement of the rules, there is no room here to provide any concise overview of the facts and issues but most of the latter

have extremely important societal effects, namely, whether Canada will remain a free and democratic society, or, ready to become a dictatorship forever. The sixth ground on page 3 above, in the Notice of Motion, is about a policy that paralyzes section 7.

of the Access to Information Act and the person of the Commissioner, in order to grant delays of months or years in the ministries’ decision-making process. Therefore, such (past) policy simply wants to bring misery for Canadians by endless

red tape. Please note that the sixth ground has not been before the judges in the courts below. As for the clearest description of the issues and controversies regarding the SCC Registry and section 61. of the Supreme Court

Act, please do not hesitate to refer to a diagram that is shown on several tabs of the applicant`s website named www.correctingworldhistory.com – a picture tells more than hundred words.

The appellant – applicant is apologizing for this hasty style and the possible grammatical and other errors in this whole submission. He is not a superman, only a humble and concerned average Canadian citizen with good intentions towards the country

and its courts. PART II – A List of Constitutional Questions in issue (drafted by Zoltan A. Simon) - Whenever error in law is alleged, does the legislation require

the administrators of the SCC Registry to refuse the filing of any Notice of Appeal under section 61. of the Supreme Court Act, R.S.C. 1985, c S-26, and prevent it to get before the panel of nine SCC judges, because

(a) Errors in law practically never happen in the lower courts; (b) The wording of s. 61. reveals that it applies only to criminal cases;

(c) Subsection 40.(1) of the Supreme Court Act always overrides s. 61. whenever error in law is alleged;

(d) The French version of s. 61. means that the proper proceeding, when error in law

is alleged, is automatically by application for leave to appeal; (e) There is an error in the wording of ss. 40.(3), so the word “appeal” shall read

as “application for leave to appeal” and, therefore, the same applies to ss. 40.(3);

(f) The four categories listed under “proceeding” in paragraph 2. of the Rules of the Supreme Court of Canada,

SOR/2002-156, are so vague or controversial that only the Registrar of the Supreme Court of Canada is able to decide about the proper

proceeding; or (g) The employees of the SCC Registry must obey another enactment that is in conflict

with s. 61.? 2. If the answer to Question 1 is in the affirmative, which specific enactment renders s. 61.

of the Supreme Court Act invalid or inoperative? 3. Can a decision – instead of an order – of the SCC Registrar expressed in a personal

letter sent to an appellant, following such situation above involving s. 61., forbid the application of Rule 78.(1) of the Rules of the Supreme

Court of Canada, SOR/2002- 156, and also override section 52. of the Supreme Court Act, R.S.C., 1985, c. S-26, so

in reality the Registrar shall exercise exclusive ultimate appellate jurisdiction in Canada? - Is the SCC Registry or its administrators allowed

to contravene Subsection 17.(1) or 17.(4) of the Financial Administration Act, R.S.C., 1985, c. F-11, by failing to pay to the credit of the Receiver General public monies including $500 as security deposit in case

of appeals under s. 61., particularly in cases where the Crown considers those appeals vexatious and abuses of process, without a scintilla of chance to succeed?

- If the Vancouver Registry of the

Supreme Court of British Columbia would refuse to file an Amended Notice of Civil Claim because the instant party submitting it is not represented by a lawyer and has no accessible address within 30 kilometres of the Registry, only an accessible address in

Alberta, an email address that had originated in British Columbia, and a fax number in Alberta, would such refusal based on the rigid and non-remedial interpretation of Subrule 1-1 (1) regarding “accessible address” and/or Subrule

4-1 (1)(b)(ii) of the Supreme Court Civil Rules, BC Reg 168/2009 requiring both an accessible address in British Columbia and a fax number or an e-mail address, all in British Columbia infringe the party’s mobility rights guaranteed

by s. 6. (2) of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, his equality rights against discrimination primarily on basis of residence guaranteed by ss. 15.(1) of the Charter, or ss. 24.

(1) of the Charter (since no court could grant any remedy to a party that has no file in the registry of that court)?

- If the answer to Question 5 is in the affirmative regarding at least one infringement

on the three sections listed, is the infringement a reasonable limit prescribed by law as can be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society under s. 1. of the Charter?

- Does

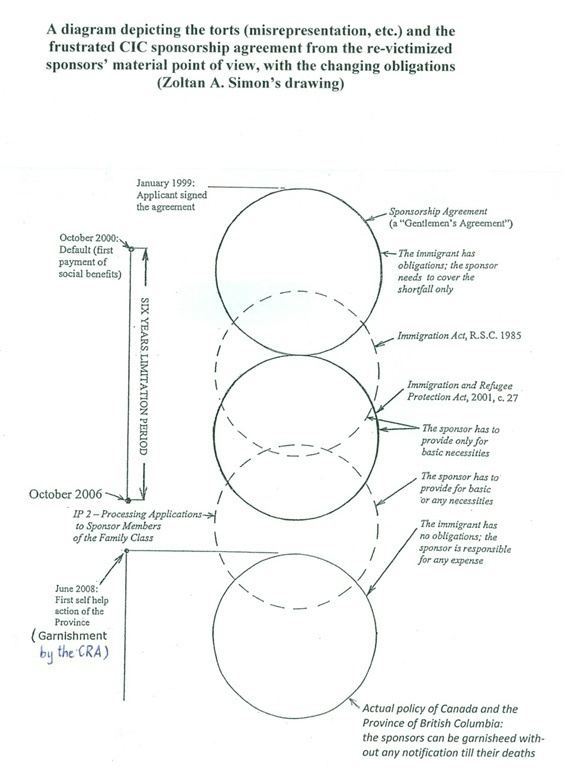

the CIC policy called “IP 2 Processing Applications to Sponsor Members of the Family Class”, by mentioning five times the word “contract” (referring to a sponsorship undertaking between “the Minister” and a sponsor)

override ss. 132. (4) of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations, SOR/2002-227 that is silent about a contract and only mentions an agreement that includes two statements and a declaration?

- In the light that the Crown has no contract with the family class sponsors, at least not with the instant appellant, is the legal principle that strangers to a contract do not have contractual rights and cannot claim damages under that contract,

as expressed in Bilson v. Kokotow et al., 1975 CanLII 771 (ON SC), and in Bilson et al. v. Kokotow et al., 1978 CanLII 1632 (ON CA), a.k.a. 23 O.R. (2d) 720 [where leave

to appeal to SCC was eventually refused], still valid in Canada?

- If the sponsors are not notified of the default and have no means to prevent a ministry to grant social assistance benefits to the sponsored persons

unlawfully, so the sponsors’ only efficient solution to prevent a default with absolute certainty would be the forcible confinement of the sponsored person(s), would this circumstance or requirement render a sponsorship agreement in the family class

void ab initio as its fulfilment would contravene ss. 279. (2) and ss. 279.01 (1) of the Criminal Code and the doctrine or maxim of ex turpi causa?

- If

the defaulting sponsors in the family class do not receive notifications of their alleged debts within the limitation period of six years after the default, they are not subject to a spousal or child support order of a court, and ss. 127.(1)

of the Criminal Code does not apply to them, could their punishment for such “offence” under the IRPA or the IRP Regulations by their forced separation from their spouses or children for a decade or forever be qualified

as “cruel and unusual treatment or punishment”?

- If the answer to Question 10 is in the affirmative, is the infringement on sections 11. and 12. of the Canadian Charter

of Rights and Freedoms a reasonable limit prescribed by law as can be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society under s. 1. of the Charter?

- Does the CIC policy called

“Memorandum of Understanding (MOU)” between the CIC and the CRA, issued in 2006, have the power to override any paragraph of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act or the Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations?

- Could the MOU’s paragraph “WHEREAS section 146 of IRPA provides that an amount or part of an amount payable under this Act that has not been paid may be certified by the Minister without delay…”

– quoted in the MOU out of context without its important preamble “COLLECTION OF DEBTS DUE TO HER MAJESTY” be construed as – contrary to s. 13. of the Interpretation Act, R.S.C., 1985, c. I-21 –

“Whenever the Minister wants to collect a “debt” (by garnishment), the Minister may optionally file a certificate in the Federal Court only for fun, but the Minister would be in the same position and have the same rights without making that

step”?

- If the answer to Question 13 is in the affirmative, but since such misinterpretation violates ss. 15 (2)(a) of the said Interpretation Act (since a contrary intention

appears) and indirectly infringes on several Charter rights, is the infringement a reasonable limit prescribed by law as can be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society under s. 1. of the Charter?

- Can ss. 145. (3) of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA) be interpreted by extrapolation as “A debt or uncertified debt claim may be recovered at any time”?

- Is there a clear legislative intent expressed in the laconic ss. 145. (3) of the IRPA (interpreted or misinterpreted as a debt may be certified at any time, even after the end of the 6-year

limitation period) to render ss. 146. (1) (b) of the IRPA – regarding the prescribed 30-day limit – invalid, while to place the whole IRPA above subsections 3 (5), 3

(6), and 9 (1) of the Limitation Act [RSBC 1996] Chapter 266, also above section 32. of the Crown Liability and Proceedings Act, and ss. 39. (1) of the Federal Courts Act, in order

to make all those enactments, plus the case law concluded by the SCC in Markevich v. Canada, [2003] 1SCR 94, 2003 SCC 9 (CanLII) invalid or inoperable?

- Since the Crown is unable to prove that a contract

or agreement has been signed by the ministers or their representatives with each sponsor in the family class, may the legislative intention, particularly the use of the word “may” instead of “shall”, expressed in ss. 145.

(3) of the IRPA be reasonably interpreted as “The Minister or the Crown may recover every certified debt claim on the basis of damages in tort that involved fraud in order to get social benefits – for example when the sponsor

or/and the sponsored person declared that they lived separately while they resided together – and the recovery may take place after the expiry of the prescribed limitation period because the Crown’s right to sue in tort is not extinguished after

that period?

- If the previous family class sponsorship of the instant appellant was filed in January 1999, the sponsored immigrants landed in Canada in December 1999, a default [as defined by ss. 135.

(a)(i) of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations] took place in October 2000 under the Immigration Act, the Minister or the Crown has not notified the sponsor until 2007, no ministerial certificate has ever been filed

in the Federal Court, the sponsor has never admitted any debt and has not made any payment, the Crown has never taken him to any court, the Minister has never taken a self-help action before the end of the 6-year limitation period (except that his tax account

was garnished in 2008/9, almost 8 years after the default), and all debt claims of the Crown against him have been exhausted by December 2006 pursuant to paragraphs 3 (5), 3 (6), and 9 (1) of the Limitation

Act [RSBC 1996] Chapter 266; in such situation what paragraph of which enactment of Canada would allow the resuscitation of his alleged debt after December 2006?

- If there is no provision in the laws of Canada

how to resuscitate a moot claim that has expired forever by limitation law, can section 190. of the IRPA [i.e., “Every application, proceeding or matter under the former Act that is pending or in progress immediately

before the coming into force of this section shall be governed by this Act on that coming into force.”] be interpreted that a silence and inactivity of the Crown for about eight years after the default constitutes a “pending matter” in December

2006, or, in April 2007 when Canada refused permanent resident visas for his wife and stepson?

- Is there any provision in the laws of Canada that renders ss. 118.(2) of the Immigration Act

(in the Revised Statutes of Canada, 1985, Volume V) inoperable or invalid in a case described at Question 18 above when the default happened in October 2000 under the Immigration Act, before June 28, 2002 when the IRPA came into

force?

- Is the watershed decision of the SCC in Canada (Attorney General) v. Mavi, [2011] 2 SCR 504, 2011 SCC 30 (CanLII) still governing in similar family sponsorship cases, so the mentioning of ministerial

certificate (seven or eight times) with the notification of the sponsors as requirements for the Crown in that verdict are still valid?

- Can the repeated wording, “under this Act” [i.e.,

the IRPA] in ss. 145.(1)(a) and (b), and ss. 146.(1) of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act be lawfully interpreted as “under this Act and the previous Immigration Act, 1976[-1977]” by

the insertion of a few words?

- Is the legal principle that the sponsors are not responsible before their notification for the social benefit amounts paid to the sponsored persons, as expressed in Manitoba v.

Khaleghi-Hashemian, 2002 MBQB 1 (CanLII) correct and still governing in Canada?

- Are the CIC-CRA policy called “Memorandum of Understanding (MOU)” and/or the Sponsorship Agreement

(REGS. April, 1997) on CIC form IMM 1344 C (02-98) by stating in the latter, “It is further agreed that damages will not be less than the total of all amounts actually received by the immigrant” [a prejudice claiming that the – always Canadian

– sponsors are always unreliable, act in bad faith so have 100% of the financial responsibility while the alien sponsored applicants and the Crown’s administrators are always perfect and never make errors or omissions] ultra vires the

CIC and the CRA for creating an absurd consequence that is contrary to legislative intention expressed in s. 3. of the IRPA, and/or infringe 15. (1) and/or s. 12. of the Charter in forced

separation cases wherespouses and their children are separated from each other for years or forever; for nine years in our case?

- If the answer to Question 24 is affirmative, and such social prejudice, stereotyping,

discrimination and collective punishment against the sponsors, based on nationality and profession, results in a cruel and unusual treatment for their families and violates the principles of the Geneva Conventions Act, are such infringements on (sub)sections

12. and 15. (1) of the Charter a reasonable limit prescribed by law as can be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society under s. 1. of the Charter?

- Was paragraph 4.(3) of the Immigration Regulations, 1978, I-2 – SOR/78-172 [stating, “The family class does not include a spouse who entered into the marriage primarily for the purpose of gaining

admission to Canada as a member of the family class and not with the intention of residing permanently with the other spouse.”], or its paragraph 5.(1) [requiring a continuous cohabitation with the sponsor for at least one year], paragraph

5.(2)(iii) – that the Crown never enforces due to the MOU and the sponsorship agreements – , or its paragraph 6.1 (2), [“Where a sponsor sponsors an application for landing of a member of the family

class described in paragraph (h) of the definition “member of the family class” in subsection 2.(1) – see “debt obligation” – and that member is unable to meet the requirements of the Act and these Regulations

or dies, the sponsor may sponsor the application for landing of another member of the family class described in that paragraph.”] valid for a family class sponsorship where the sponsored immigrants landed in Canada in December 1999 and a sponsorship

default took place in October 2000?

- If the answer to Question 26 is in the affirmative for any of the paragraphs cited above from the Immigration Regulations, 1978, and if a sponsored spouse has not qualified

as having been a member of the family class when the sponsorship default occurred, can he or she create a sponsorship debt in the family class for the sponsor?

- Are paragraphs 145. and 146.

of the IRPA as interpreted or misinterpreted by Crown policies inconsistent with the definition of “debts, obligations and liabilities” in ss. 3 (1) of the Court Order Enforcement Act, RSBC 1996, c 78 –

claiming that obligations not arising out of trust or contract are not debts, unless judgment has been recovered on them – also supported by paragraphs 8, 9 and Schedule 2 of the Family Support Orders

and Agreements Garnishment Regulations, SOR/88-181? [Please note that the sponsorship agreements in the family class fully or partially belong to “family agreements.” Also, the IRPA and the IRP Regulations intend to deal

with immigration, not with specific details of garnishment.]

- Does the IRPA or the Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations contain any provision that allows a province or territory to issue

an efficient document for CRA or CIC, in lieu of the required ministerial certificate filed and registered in the Federal Court pursuant to s. 146. of the IRPA, substituting the latter certificate by a single page signed

by any provincial public servant claiming that the sponsor’s debt is enforceable?

- When a provincial ministry did not make a payment of a prescribed nature or violated the laws of that province, particularly

when paying benefits for ineligible full time students (as in case of the appellant’s previous sponsorship) pursuant to ss. 16. (1) and (2) of the Employment and Assistance Regulation, BC Reg 263/2002, may such error of the

Crown’s administrator reduce or eliminate the sponsor’s alleged financial responsibility or debt?

- Since the word “interest” in the financial or banking sense appears only under ss. 146.(2)

in the IRPA, is it a reasonable supposition that the legislative intent was not to charge interest before the filing and registration of a ministerial certificate in the Federal Court that is approximately the time of the sponsors’ supposed

notification about their defaults or debts?

- Is the Province of British Columbia allowed to ignore and contravene sections 3. and 4. of the Interest Act, R.S.C., 1985, c.

I-15 [that prescribes an interest of five per cent per annum] and charge more than six per cent yearly interest rate on the alleged uncertified sponsorship debt in a case where the sponsorship agreement did not specify an interest rate and a non-existing contract

between the sponsor and the Crown could not contain an express statement of the yearly rate or percentage of interest to which the other rate or percentage is equivalent?

- Considering Subsection 6.(2)

of the Garnishment, Attachment and Pension Diversion Act,R.S.C., 1985, c. G-2, when a ministry of British Columbia served a garnishee summons on Her Majesty in Right of Canada [i.e., the CRA] in 2008 with a delay of almost eight years, well

after the limitation period has expired, while it could have been served on Her Majesty in October or November 2000 within thirty days after the instant appellant’s sponsorship default, was that garnishee summons properly served and effective in law?

- If public servants can interpret ss. 80.(2) and ss. 83.(1) of the Financial Administration Act [RSBC 1996] that a “certification” of a debt by any administrator

is valid without the involvement of any court, and British Columbia can garnishee the “suspect” debtor’s tax account with CRA, would such inconsistency with s. 27. of Garnishment, Attachment and Pension Diversion Act,

RSC 1985, with s. 26. and s. 45. of Family Orders and Agreements Enforcement Assistance Act, RSC 1985, ss. 146.(1) and (2) of the IRPA, and/or paragraphs 8, 9,

and Schedule 2 of Family Support Orders and Agreements Garnishment Regulations, or/and ss. 11.(d) of the Charter render the cited sections of the Financial Administration Act [RSBC 1996] invalid

in law?

- In light of the fact that the wording “judgment debtor” is found 34 times in the Federal Courts Rules but no matches show up for “other than judgment debtor”, “possible

debtor,” “suspect debtor” or “suspected debtor” by a search at all, and the situation is similar in other federal enactments, is it possible that in the laws of Canada the word “debtor” always refers to “judgment

debtor” and, therefore, a possible debtor that has never received any summons shall not be punished?

- If a sponsored spouse in the family class abandons his or her sponsor within a year of continuous cohabitation,

and keeps to cohabit with another boyfriend or girlfriend while gets social assistance benefits, would such circumstances turn an innocent re-victimized sponsor into an “offender” legally? [Sub-question 36 (a): If the answer for Question 36 is

“yes,” and there is no ministerial certificate on file in the Federal Court for seven years after the default of the garnisheed sponsor in the family class, is that a contravention of ss. 11. (a) of the Charter? Sub-question

(b): If the answer for the previous sub-question 36 (a) is in the negative, and the Crown is punishing such non-offence by the forced separation of a family for seven or more years, is that considered a cruel or unusual punishment or treatment that contravenes

section 12. of the Charter?

- If a memorandum of fact and law was served and filed by the Government of Canada in the case “Docket: A-367-12,” with a delay of 33 days after the

deadline set by Rule 346. (2) of the Federal Courts Rules, SOR/98-106, and the FCA Registry accepted its filing while the Federal Court found Mr. Abdessadok’s 24-hour delay in filing his submission unacceptable in Abdessadok

v. Canada (Canada Border Services Agency), 2006 FC 236 (CanLII), and such adverse treatment between the Crown and the instant self-represented appellant (as an unjustified or unjustifiable distinction between the powerful and the weak) infringe on s.

15.(1) of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, is such infringement demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society pursuant to s. 1. of the Charter?

- If the Courts Administration Service or the Chief Justice of the FCA ignored for good the filed Notice of Appeal of an interlocutory order [dated 30 May 2013, Docket: A-367-12 above] issued by a FCA judge, without ever assigning a judge to review the appellant’s

arguments that claimed palpable and overriding error(s) in law, is such solution consistent or harmonious with ss. 8. (2)(c) of the Courts Administration Service Act and s. 3. of the Federal Courts Act,

“for the better administration of the laws of Canada?

- If the Registry of the Supreme Court of Canada, by contravening s. 61. of the Supreme Court Act, refused the filing of a proper

Notice of Appeal under s. 61. [related to questions 37 and 38 above], preventing the appeal be heard by the panel of nine SCC judges, does it mean that the FCA order of 30 May 2013 [Docket: A-367-12] is final, the word “service”

in ss. 346. (2) of the Federal Courts Rules is “absurd” and the words of that subrule shall be interpreted as “Within 30 days of filing” instead of “Within 30 days after service”? [Note: Particularly

in light of s. 3 of the Federal Courts Rules and the fact that parties do not fight with a Court but with each other, and a delay in serving a document may cause huge financial losses for the opposing party or parties but not for

the Court.]

- If the Registry of the Supreme Court of Canada, by contravening s. 61. of the Supreme Court Act, refused the filing of a proper Notice of Appeal under s. 61.

as the instant appellant’s last step againstthe “Tremblay-Lamer principle” (see Docket T-1029-12, the order of the Honourable Madam Justice Tremblay-Lamer dated 20 July 2012, stating that “No action for damages premised on a hypothetical

administrative decision can succeed because no damage has yet materialized”) is such legal principle valid and final in every case where the Crown threatens a party, person or firm with a possible future unlawful administrative decision? [Note:

Thus, is it now widely acceptable for the Registrar of every court in Canada to post a memo stating, “Administrators of the Registry that file any pleadings against the Crown may lose their jobs without notice and severance payments”, or, may every

A.G. of each province rightfully post a memo saying, “Salaries of judges that grant costs or damages to a party against the Crown may lose all their benefits and severance payments, and their salaries may be cut by 25%?]

- If the answer to Question 40 is in the affirmative and the Crown may apply coercion and intimidation freely and openly, partly with the aim of corrupting Canada’s public servants and the whole society, is such infringement on values fundamental

to a free and democratic society a reasonable limit prescribed by law as can be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society under s. 1. of the Charter?

42. Do the administrators

or officers of the Office of the Information Commissioner of Canada have the right to usurp or reduce the power of the Information Commissioner by claiming that she (Ms. Suzanne Legault) has no mandate under s. 7. of the Access

to Information Act to investigate complaints due to the CIC’s failure to provide information within the prescribed 30 days to Service Canada or/and a citizen despite that the Department of Citizenship and Immigration is listed under Schedule I,

the request was for a single record easy to find, and CIC has not filed a notice of request for extension of time limit?

The front page of the Notice of Civil Claim that Z.A. Simon and Z.H. Zhong filed the Attorney General of Canada and the Attorney General of BC in May 2014. Please refer its complete text below the following "Summary of two unique court cases".

An Application Response and its Affidavit follow this Notice of Civil Claim.

The front page of the Notice of Civil Claim that Z.A. Simon and Z.H. Zhong filed the Attorney General of Canada and the Attorney General of BC in May 2014. Please refer its complete text below the following "Summary of two unique court cases".

An Application Response and its Affidavit follow this Notice of Civil Claim.

SUMMARY OF TWO UNIQUE COURT CASES AGAINST MR. HARPER'S POLITICAL-CRIMINAL PYRAMID SCHEME

This summary is for the perusal of the leadership of the Canadian opposition parties (and the reasonable members of the CPC if any) in order to introduce a no-confidence vote against the dictatorship of Stephen Harper in Parliament. Alhough the conservative

majority may defend Mr. Harper's unlawful policies by standing ovation there, even a failing no-confidence vote could call the public attention to the end of Canada's democracy and to a flourishing corrupt dictatorship. Mr. Harper's Cabinet is the first

one since 1867 that operates openly against the will of Parliament. It keeps violating more than forty laws of Canada since 2006. All admisitrators of many federal ministries and agencies blindly obey the unlawful policies of Harper's Cabinet unconditionally

-- just like soldiers, by a political-criminal pyramid scheme. Thus, Canada's federal administrators have been prostituted. Z.A. Simon's two court cases below list most of those violations. The government's unlawful policies are aimed primarily

against the most vulnerable segments of society: the seniors applying for OAS benefits, the re-victimized sponsors whose lives have been ruined twice although they bear most of the burdens of new immigration that is crucial for Canada's labour market, ...

besides the well known issue of 1,200 missing or murdered aboriginal women, the miserable treatment of veterans as welfare bums, or the policies creating permanent damages for the Canadian environment. This web page contains major areas

of tort law involving the Crown as follow: A. The Crown's tort system originating from the violation of s. 145. (1) and (2) of the IRPA (Immigration and Refugee protection Act): the re-victimized sponsors suffer unlawful

garnishment AND by the separation of their families WITHOUT filing any ministerial certificate at the Federal Court as reqired by law. Hundreds or thousands of re-victimized sponsors and their families are suffering irreversible damages due to this tort and

conspiracy; B. The Crown turns Canada's court system upside down by pressuring the Registrar of the Supreme Court of Canada not to comply with section 61. of the Supreme Court Act where error is alleged at the lower court(s).

Instead, the Registry's administrators always automatically apply section 40. (1) of the same Act (which paragraph is silent about errors in the lower courts). By this simple tort, the Registry acts as an agent or puppet

of the PMO: the administrators block all the cases of high societal importance from the panel of nine supreme judges of Canada. This means that the "duo" of any present and future PM and the SCC Registrar is usurping the power of the nine SCC judges, hermetically

isolating those judges from the rest of Canada. This means that Canada is approaching a stage where those top two persons control the whole court system. Thus, our country soon could become the prey of any dictator, either extreme right or left, stalinist,

fascist, religious fanatic, or Waco-style. This is a recipe for a civil war unless the Crown gives back the power to the nine judges of the SCC; C. The same conspiracy (that includes the federal Cabinet's members right now) has got perfect control

of the Court Administration System - that is apperantly led by Mr. Gosselin and/or Mr. Blais, C.J. of the Federal Court and the Federal Court of Appeal. Thus, the orders coming from the PMO through those administrators are blocking the way of any

party that has claims against the Crown. The administrators often misinterpret the orders of the judges, deny or delay the filing of otherwise acceptable pleadings, cut out dozens of pages from the documents by blade or scissors [though the judges

ordered certain pages or paragraphs to be struck by horizontal lines], etc. The Crown's pleadings are always accepted by the registries for filing even despite of an unjustifiable delay of several weeks or months while the administrators refuse

to file documents of Canadian individuals submitted by a delay of 24 hours. Although most of the FC and FCA judges are unbiased, the torts of the registries often prevent them from seeing the overall picture and disable them to deliver unbiased judgments;

D. A few provinces apply the "assize" system in the courts' scheduling departments. Such word does not show up in any legislation and contravenes section 15. (1) of the Canadian Rights and Freedoms by discrimination based

on residence or province. An "assize" is normally two weeks - sometimes one week - long. An assize is not a date so its application violates the rules of the courts. The provincial assize system means that the court's administrators leave the

small parties in total darkness, uncertainty, and suspense, creating them a huge expense. Say, a plaintiff of Nunavut files a claim in the Supreme Court of BC. He or she gets a notice of a week or less instructing him or her to show up at a hearing

in BC. The plaintiffs may lose their jobs for failing to give notice to their employers. They need to buy a much more expensive airplane or bus ticket and book an expensive hotel in the last minute. The Crown, of course, knows the exact date of the

hearing a month ahead since the A.G. controls the administration of the courts. Let alone that if the parties coming from far away (like Nunavut) would lose their cases they may have to pay the transportation and hotel costs of the Crown Counsel(s) for

10 nights or so, plust their man-hours for 240 hours. The parties may need to wait for nine days and the real hearing would take place on the tenth day only. Thus, it seems, the assize system is planned to discourage every party from suing the Crown,

or, make them face unsurmountable financial and other difficulties. (A local resident could sit for ten days at the door of the courtroom and could be available by a ten-minute notice for a hearing. This is a clear discriminiation and violation of the Charter

against non-residents.) E. Finally, an extremely important issue that allows the Harper Government to eliminate time as a factor by snatching the power of the Information Commissioner of Canada. Section 7. of the Access to Information

Act obliges each goverment office or ministry to respond to inquiries within 30 days afteer the request. Mr. Harper's Cabinet has prohibited to the Information Commissioner to supervise violations of this Act. The Harpies

immediately utilized this tort by ignoring new applications of seniors for their pension benefits like Old Age Security benefits. [Zoltan A. Simon turned 65 in May 2014 and the federal government is sitting on his pension monies and using them.

He has found three more persons in Red Deer that are suffering from similar treatments by waiting for a year or two for the first pension benefits.] The government is contravening several sections of the Charter by such cowardly and oppressive

strategy. How could thousands of seniors survive for more than a year after the filing of their application without receiving their well deserved cheques? Well, these are just a few examples of the flourishing Crown torts in Canada.

(Are we, indeed, the most livable counrty of the world???) Re-victimized family class sponsors, starving seniors and veterans, 1200 missing native women, and self-represented litigants seem to be the main targets of Mr. Harper's and the Crown's catasrophal

policies. If the opposition parties quietly sit back on their laurels for the next 11 months Canadians could see major deterioration of their lives. Harper my win by using a more sophisticated "robocall" campaign. He may pass a new law in Parliament stating

that his decrees would govern and Canada's legislation is just a rough guidelines that does not need to be followed. The CPC may skip the elections in the autumn of 2015. Tanks with the PM's painted image on them could rumble on our streets after October

2015. The RCMP and the army may take different sides and may start shooting at each other during a civil war, during which certain provinces may declare independence from the rest of Canada. Harper may prorogue Parliament for the third time: this time

for good. Since dictators do not need good judges, only corrupt puppets, Mr. Harper may send the majority of our judges to welfare while giving extreme power to each Registrar of every Canadian court that could make the final decisions. Or,

the registrars would be prohibited from filing any claim against the Crown without the PM's special permission. This is a Stalinist approach that would fit Harper's past criminal achievements and future political ambitions. Canada would irreversibly become

the first or second country of the so-called New World Order where the top 0.5% treats the other 99.5% as slaves. (In my opinion, more mysery for the 99.5% does not automatically mean a better or richer life for the top 0.5%.) Pursuant

to Murphy's Law if there is a chance that something wrong may happen it will happen. It is time for every Canadian to start thinking and acting for a better solution.

New and unique court cases about Crown torts

No. 4756

GOLDEN Registry In the Supreme Court of British Columbia Between Zoltan Andrew SIMON and Zuan Hao ZHONG Plaintiff(s)

and Attorney General of Canada and Attorney General of British Columbia Defendants NOTICE OF CIVIL CLAIM

This action has been started by the plaintiff(s) for the relief set out in Part 2 below. If you intend to respond to this action, you or your lawyer must (a) file a response to civil

claim in Form 2 in the above-named registry of this court within the time for response to civil claim described below, and (b) serve a copy of the filed response to civil

claim on the plaintiff. If you intend to make a counterclaim, you or your lawyer must (a) file a response to civil claim in Form 2 and a counterclaim in Form 3 in the above-named registry of

this court within the time for response to civil claim described below, and (b) serve a copy of the filed response to civil claim and counterclaim on the plaintiff and on any new parties named in the counterclaim. JUDGMENT

MAY BE PRONOUNCED AGAINST YOU IF YOU FAIL to file the response to civil claim within the time for response to civil claim described below. Time for response to civil claim A response to civil claim must

be filed and served on the plaintiff(s), (a) if you were served with the notice of civil claim anywhere in Canada, within 21 days after that service, (b) if you were served with the notice of civil

claim anywhere in the United States of America, within 35 days after that service, (c) if you were served with the notice of civil claim anywhere else, within 49 days after that service, or (d) if the time

for response to civil claim has been set by order of the court, within that time. Claim of the Plaintiff(s) Part 1: STATEMENT OF FACTS - The plaintiffs are Zoltan Andrew

SIMON and his wife Zuan Hao ZHONG (Zhong Zuan Hao in Chinese). The latter is citizen of the People’s Republic of China. They are pleading in their personal capacity as two individuals forming a single party since Z.A. Simon is representing Ms. Zhong

and himself. Their mailing address for service is the same. Zoltan A. Simon is Canadian citizen since 1979. In the following pleadings the word “plaintiff” always refers to Zoltan Andrew Simon, the main plaintiff. Ms. Zhong and her son Mr. Ye signed

an affidavit before a state notary public office in China, authorizing Zoltan A. Simon to represent them in any court case or hearing in Canada.

- The two Defendants are: A: The Attorney General of Canada in his representative capacity (representing

four ministries and two court registries of Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada) and B: The Attorney General of British Columbia (representing four provincial ministries of Her Majesty the Queen in Right of British Columbia). Both Defendant parties are

sued in their representative capacity. There are no individual defendants.

- Both defendants include Canada’s Crown servants, employees, agents and/or departmental or other officers and ministers responsible for the lawful operation of the CRA

(Canada Revenue Agency) – probably the Minister of National Revenue or Minister of Finance, or both – and the CIC (Ministry of Citizenship and Immigration Canada), also the Ministry of Justice and/or the federal authorities responsible for the

lawful operation of the Courts Administration Service, particularly the FC/FCA Registry in Edmonton, and the Ottawa Registry of the Supreme Court of Canada. As for British Columbia, four branches of the BC Government are also included as follow: RSBC (Revenue

Services of BC), Ministry of Housing and Social Development, Ministry of Finance, and Ombudsman BC.

- The key officials of the Crown that have caused the damages in different torts for the plaintiffs will be called “honourable tortfeasors”

below, since it is hard to find a better definition for this group. It includes the ministers of the CIC (Citizenship and Immigration Canada, or Citizenship, Immigration and Multiculturalism): Mr. Monte Solberg (January 2006 to January 3, 2007), Ms. Diane

Finley (January 4, 2007 to October 29, 2008), Mr. Jason Kenney (October 30, 2008 to July 14, 2013), and Mr. Chris Alexander (from July 15, 2013); the ministers of Human Resources and Skills [or Social] Development: Ms. Diane Finley (January 2006 to January

4, 2007 and from October 30, 2008 to July 15, 2013); ministers of Department of Justice [Ministers of Justice and Attorneys General]: Mr. Vic Toews (February 6, 2006 to January 3, 2007), Mr. Rob Nicholson (January 4 2007 to July 14, 2013), and Mr. Peter MacKay

(since July 15, 2013). The Commissioner and Chief Executive Officer, the head of the CRA, also belongs to this group. Or, rather, the Deputy Commissioner named Mr. Bill Baker who had knowledge of the matters. Further members of this honourable group are Mr.

Stephen Harper, Prime Minister, Mr. Wally Oppal (A.G. of BC), Ms. Penelope Lipsack (Counsel to the Government of BC was also involved and even sued by the plaintiff), Mr. Gordon O’Connor and Jean-Pierre Blackburn, both Minister of National Revenue, Ms.

Sylvia Dalman (CRA), and Ms. Sharon Shanks (Service Canada). On behalf of Ombudsman BC, R. Brown and Ms. Judy Ashbourne may be mentioned. As for the employees of the Registry of the Supreme Court of Canada, Mr. Roger Bilodeau, Ms. Mary Ann Achakji, Ms. Barbara

Kincaid, Ms. Nathalie Beaulieu and Mr. Michel Jobidon belong to this group of tortfeasors. Finally, Mr. Daniel Gosselin is a tortfeasor representing the Courts Administration Service. The Attorneys General of Canada and BC have vicarious liability for the

acts, errors, and omissions of all these officials listed above.

- The plaintiffs are suing the federal and provincial Crowns that are, and have been, in all material times, vicariously liable for the acts and omissions of their public servants –

including the ministers listed above – in their representative capacities.

- The plaintiff is not suing Her Majesty the Queen in her personal capacity. Please note that the word “Minister” in the entire pleadings includes a Deputy

Minister and the predecessor(s) of that Minister involved in the matters before this Honourable Court.

- The plaintiff is reluctant to show the names of the SCC Registry’s administrators involved. In the past he has listed them in the style of

cause on the front page. It resulted that they declared themselves a party independent from the Crown as the “SCC Party.” Such trick has caused extreme difficulties for the plaintiff, with more costs at each step. In the instant pleadings at bar

their names are not shown in the style of cause. However, the plaintiff is suing the Crown (HMTQ) that is vicariously liable for their torts, acts and omissions. Should they hire a separate Counsel, they shall submit an affidavit stating that they are not

– or have not been – servants of the Crown. (In that case, the plaintiff would add the charge of perjury against them.)

- The plaintiffs assert that all of the public servants of Canada and BC in question made their acts and omissions during

their employment with the Crown, in all material times. (The Crown is free to sue any of them as third parties if they acted in their personal capacity.)

- This is a damage claim of the plaintiff for his “personal” injuries, including mental

suffering, anguish, loss of enjoinment of life, constant headaches and sleeplessness, loss of self-esteem and identity as a Canadian citizen, reduced life expectancy, and cruel or unusual punishment (as a Charter violation) for his family by his wife’s

unlawful and forced separation from him for more than seven years. Also, claims are pleaded for restitution, declaratory relief, for Charter violations and punitive damages.

- The torts against Zoltan A. Simon and his wife Zuan Hao Zhong

took place in Ottawa (Ontario), Greater Vancouver and Victoria (British Columbia), and Hong Kong (Consulate General of Canada), between January 1999 and May 23, 2014 or present.

- The plaintiff has a personal tax account (S.I.N. 718 XXX

XXX) with both Defendant. Also, he had an active tax file with the Province of BC between 1976 and 2002. Both plaintiffs have a shared CIC file, with Client #20925897, KIT ID #200710018372, in the Mississauga Case Processing Centre. Therefore, in all material

times since January 1999, the Defendants owed a standard duty of care obligation to Mr. Simon, and since February 2007 to Ms. Zhong.

- Ms. Zhong, one of the plaintiffs, was born on November 26, 1962 in Qingyuan, Guangdong Province, China. Presently

she is a homemaker, with a modest monthly pension income.

- The main plaintiff, Zoltan Andrew Simon, is a self-represented litigant. He was born in Budapest, Hungary, on May 26, 1949. His original professions were geologist and land surveyor, with diplomas.

He came to Canada in 1976 as a landed immigrant and worked in Canada – mainly in civil, mining, and railway engineering in BC – until 2002. He worked in Ontario till 2007 as a textile operator, finally since 2008 as a security officer in Alberta.

He is author of several published books about world history. He is resident of Red Deer, Alberta.

- The plaintiff’s two children were born in Vancouver: Rita (30) and Eric (28). Both of them are living in the Greater Vancouver area and have sons.

In 1998, when his children were not living with him, the plaintiff felt lonely and wanted to have and support a family again.

- Thus, the plaintiff married Ms. XXXXXXX Reyes in December 1998 in Honduras. She was citizen of Honduras, now Canadian. He

sponsored her with her two minor sons on or about January 4, 1999. The Defendant CIC instructed the plaintiff to sign the “Sponsorship Agreement IMM 1344 C (02-98) E” and “Undertaking IMM 1344 B (02-98) E” forms. He considered it a

moral and personal “gentlemen’s agreement” with Ms. Reyes. It did not contain the term “joint and several contract.” It was a severable bilateral agreement listing the obligations of both the sponsor and the sponsored person.

It was not a maintenance agreement. Ms. Reyes and Z.A. Simon were joint promisors towards each other.

- Ms. Reyes and her two sons arrived in Canada on or around December 27, 1999 as landed immigrants in the family class. (The DOB of XXXXXX is XXXX-XX-XX

while XXXXXXXX’s DOB is XXXX-XX-XX.) They resided in the plaintiff's rent-to-own apartment in Port Moody (BC) until January 1, 2001. Ms. Reyes spoke a basic English but they communicated mainly in Spanish. She was a healthy, smart and attractive

person, an ideal candidate for a job in Canada. She did not work before 2005. [Therefore, pursuant to the BC law, she did not qualify for any social benefit, only for a hardship assistance, loan or similar.] The plaintiff worked as a self-employed owner-operator

delivery driver in those days. The money that he made was sufficient to support his sponsored new family members but his wife kept spending more than his income.

- The plaintiff supported the sponsored person(s) in his home in Port Moody (British Columbia)

until January 1, 2001 regarding all costs related to dwelling, despite of his involuntary separation from Ms. Reyes after mid-June 2000, due to the following incident.

- One day, about mid-June 2000, the plaintiff had only $50 left and he had to buy

gas for his van. The sponsored immigrant wanted to take away that money but the plaintiff resisted. She started to push him around the table while hitting him and abusing him verbally, so he needed to defend himself. The RCMP of Port Moody was called but they

took no action since the sponsored boys were sleeping with the sponsor while their mother had disappeared until the morning. On the same morning, the plaintiff packed up his van and moved out, preventing further violence in front of the children. He found

a miserable room for rent (for $10 per day) where the wind blew the snow inside through the cracks in the winter. The plaintiff and Ms. Reyes did not have any separation agreement.

- In July 2000, the plaintiff tried to make peace with Ms. Reyes but

she preferred to live independently, not allowing him to return and sleep in his room. The plaintiff brought them some food occasionally. About August 2000, he sent a letter to the Case Processing Centre in Mississauga, explaining the real situation for the

CIC. As re remembers, he wrote that he loved Ms. Reyes and would support her if they formed a family, living together. He promised that he would pay all the costs of the sponsored persons related to dwelling and bills for services until January 1, 2001. (He

kept his word regarding that promise.) In his letter he stated that he had never promised to anyone to maintain two separate dwellings and, on the long run, he was unable to do so.

- Apparently the CIC forwarded the contents of the plaintiff’s

letter to the B.C. Ministry of Housing and Social Development. Thus, the Crown’s public servants had been aware of the problem long before the first social assistance payment to Ms. Reyes. (However, they have never contacted the plaintiff until 2007.)

- In or about September 2000, Ms. Reyes applied for social benefits in Port Moody, BC. The ministry involved has not sent any letter to the plaintiff and he has not received any phone call from any official either. The CIC has remained silent as well. The

Crown has not sent him any notification regarding the status of his wife’s application for social benefits.

- Apparently, she started to receive benefits from the Government of BC in October 2000. Thus, a default of the Sponsorship Agreement took

place in October 2000. Pursuant to ss. 15 (1)(a)(i), 15 (1)(b)(i), 15 (1)(c)(i), 15 (1)(d), 15 (3) and 17 (1) of BILL 14 – 1996 or BC BENEFITS (INCOME

ASSISTANCE) ACT and ss. 118. (2) of the Immigration Act, 1976 [that came into power in 1978],or, the Sponsorship Agreement, theBC Government or its Minister could have brought a court proceeding against the plaintiff but such

proceeding has never taken place. Or, the said BC Minister could have granted hardship assistance for Ms. Reyes, pursuant to ss. 4 (a). of the BC Benefits (Income Assistance) Act. Or, pursuant to ss. 9 (1)(a) of the

same Act, the Minister may have taken action if Ms. Reyes has failed to demonstrate reasonable efforts to search for suitable employment.

- In 2000 or 2001, Zoltan A. Simon fell behind his obligation to pay the monthly $300 child support

for his 15-year old son Eric (by his mother and guardian, Ms. XXXXX Ortega), residents of Surrey, BC.

- By January 1, 2001, the plaintiff lost his nice rent-to-own apartment in Port Moody, that was his investment for about two years, due to the earlier

incident with Ms. Reyes.

- In or about March 2001, the BC ministry responsible for the administration of child support started to garnishee the pay cheques of the plaintiff at Reliable Couriers (Coquitlam, BC). The said ministry sent 50% of his gross

income – about 75 or 80% of his net income – to Ms. Ortega, then wife of Mr. XXXXXX. The garnishment by the BC ministry took place unlawfully. They disobeyed the law prescribing that the portions of gross income necessary for the debtor to spend

as expenditures, in order to maintain his business, should have taken into consideration. Thus, the plaintiff ended up on welfare while two women – both supported by wealthier men – tried to garnishee him. The plaintiff tried to get help from Legal

Aid on Kingsway in Burnaby (BC) but they said his situation was too complicated. They were unwilling to assist him. (In reality, no Legal Aid office in Canada seems to be allowed to help the victims of government torts.)

- By the summer of 2001 the

plaintiff understood that the smart and attractive Ms. Reyes had found a boyfriend in the person of XXXXXXX, a wealthier neighbour living on the same floor. The boyfriend supported her and her sons financially for five years, until he ended up in

bankruptcy due to their overspending.

- Therefore, although the plaintiff wanted to work and support his family members, he was disabled to do so. [In general, an average person cannot survive on 20 or 25% of his or her net income.] The plaintiff

was on social benefits for 11 months and he filed for bankruptcy at that time. He hated to appear as a “welfare bum” and rather “fled” to a pen-friend overseas. He left BC on January 31, 2002 for Brazil where he resided in exile

for 19 months. In the meantime, most of his documents, books and notes – that had been stored in the house of his daughter’s schoolmate – have been thrown to the garbage or perished.

- The plaintiff, Z.A. Simon, divorced Ms. Reyes

in January 2002 as he remembers.

- Regardless the uncertainty of his future, the plaintiff returned to Canada from Brazil. He was afraid to return to BC so he lived at a homeless shelter near Toronto or Brampton, for about two months, then he moved

to Arnprior, ON.

- During the year 2002 and/or 2003 the debtor’s driver’s licence was suspended but was reinstated when he became a discharged bankrupt upon his return from Brazil.

- On or about November 18, 2003, the plaintiff received

a response signed by the Hon. Martin Cauchon, then Canada’s Minister of Justice. The letter was polite but contained only beautiful words without any solution regarding the BC ministry’s unlawful garnishment action.

- Probably

early in 2004, he filed a sponsorship application for Ms. BXXXXXXX, citizen of Brazil. More or less a year has passed but the CIC remained silent about it. In January or February 2005, Ms. BXXXXXXX left him for an 89-old rich man (who died two

years later). Therefore, the plaintiff sent a letter to the CIC Processing Centre and cancelled his proposed sponsorship for her. This took place in or before March 2005. At that point the Crown (CIC and BC) showed no indication that the

plaintiff would have owed any debt to any ministry. (Later he understood that the federal policies regarding sponsorships were in a confused state in those days.)

- In March 2005, the plaintiff sent a birthday card to Ms. Reyes. Soon he learned that

she had just broken up with Mark, her boyfriend. The plaintiff suggested to Ms. Reyes to cohabit again and form a family but she wanted to remain independent, living separately.

- Ms. Reyes improperly and unnecessarily received social benefits from

the Province of B.C. from October 2000 to June 2005 but the Crown failed to inform the plaintiff about it. She received social benefits for almost five years while the administrators of BC sent her to several English language courses for about four years.

This way the Province unilaterally removed the sponsored person from the work force of BC. A single mother cannot work after a full time study five days a week: she had to spend some time with her sons.

- In or about June 2005, the plaintiff learned

from Ms. Reyes that the proper BC Ministry started to encourage her to get employment, so she has accepted the first job offered to her by the agents of that Ministry.

- In 2006, the ministers or leaders of the CIC and the CRA signed agreements

with each other in order to facilitate the garnishment of the sponsors in default. They published two documents, named “IP 2” and “MuO”, primarily for the use of their administrators. These two policies disagreed with

the legislation but enabled the administrators to eliminate the requirements as for the Court’s involvement since the documents emphasized only the Crown’s rights and not its obligations, claiming that every sponsor had a valid contract

both with the Minister of CIC and the sponsored person(s). Please refer to paragraphs 5.18, 6.9, 12 and 16 of the IP 2 policy. Under paragraph 5.29 the text goes, “…may be recovered from the sponsor and/or co-signer.” Those policies

did not mention or emphasize the need for the Court’s involvement anymore.

- In 2006, the Crown (Canada and BC) failed to notify the plaintiff about this important material change (that the Crown had become a party to his Sponsorship Agreement,

and that the Agreement had become a contract). Therefore, the Crown prevented the plaintiff from studying the relevant legislation, or, to consult a lawyer. For this reason, he was disabled to defend himself at the IRB/IAD hearing, resulting that he has been

separated from his present wife between April 2007 and today.

- The plaintiff was unaware of those policies (IP 2 and MuO) until about 2008 or 2009. He has never received or signed any contract form with any ministry or government.

He wanted “to enter into a legally binding Agreement” with BC or Canada but no one sent him anything like that to sign. The Defendant Crown has not been signatory to any written contract or agreement with the plaintiff at all.

- In the summer

of 2006, the plaintiff began a correspondence with Ms. Zuan Hao ZHONG (a.k.a. Zhong Zuan Hao in Chinese). They had common goals, including getting married soon and have a baby. Thus, they got married in December 2006 in Guangzhou City, in the People’s

Republic of China. The plaintiff filed the necessary documents to sponsor his new wife, Ms. Zhong (d.o.b. XXXX-XX-XX) and her 15-year old son, Jian Feng YE (d.o.b. XXXX-XX-XX).

- Due to some red tape in both countries and the numerous required documents,

the plaintiff submitted his Sponsorship Agreement and Undertaking forms with the supporting material to the CIC Processing Centre on or about February 15, 2007. He attached a bank draft in the amount of $1,190 for the required fees. Since then the CIC is using

that money.

- On or about March 30, 2007, he received a letter from the CIC Processing Centre in Mississauga. In it, Officer RS stated, "We are pleased to advise that you have met the requirements for eligibility as a sponsor…” However,

the same letter indicated that the Consulate General of Canada in Hong Kong – the visa office as the ultimate authority – may not accept their application in case of any debt to the Crown. [Strangely, this information seemed to indicate that the

CIC Case Processing Centre had been unaware of the plaintiff’s sponsorship debt, and only the proper visa officers abroad had been able or allowed to make a final decision.]

- Soon the plaintiff learned that the application for the permanent

Canadian residence of his wife and his stepson had been dismissed. Since they have passed their medical tests, the only reason of the refusal was the alleged sponsorship debt of the plaintiff. This circumstance has been stated clearly on the documents

issued by the Consulate General of Canada in Hong Kong, dated on or about April 26, 2007. The Canadian authorities sent a similar statement to Ms. Zhong at about the same time.

- On or about March 20, 2007, a form named “Social Services Information

Request” was sent from the CIC Processing Centre to the Ministry of Employment and Income Assistance of BC. (The Plaintiff received its copy after a long delay.) The printed name of the official does not appear on the form and the signature is missing

above the proper line. It is testified as “In accordance with the provisions of the federal/provincial Memorandum of Understanding to the best of my knowledge the above information is true and correct.” However, that MoU was not a legal

document. The officer has not testified that the Information Request satisfied the requirements of the IRPA and/or its Regulations and that a debt had been certified by the Minister against Zoltan A. Simon.

- In

May 2007, the plaintiff(s) appealed the Immigration Officer’s decision at the IAD (Immigration Appeal Division) of the IRB (Immigration and Refugee Board). [He appealed to the Federal Court but he lost his immigration-related case in 2010. Canada’s

laws do not allow an appeal. There is no Court in Canada that would examine his situation. Due to this federal-provincial tort, his wife and stepson could never immigrate to Canada.]

- In 2007, the plaintiff – the innocent party – rescinded

his sponsorship agreement.

- The plaintiff had a court hearing in 2007, in Ottawa, under Federal Court File No. T-1758-07. Since he was waiting for his IAD hearing, his claim was dismissed as abuse of process.

- The plaintiff

pleads innocent in any breach of contract because he was unaware of any contract or agreement with the Crown. Also, he was unaware of the dollar amounts and number of months during which Ms. Reyes, the sponsored immigrant, received social benefits in Canada.

After a private investigation of six months, in or about October 2007, he received the first notice about the dollar amount of his alleged “sponsorship debt.” It was over $38,000. However, so far to date, British Columbia or Canada has not filed

any claim against him at any Court during all material times.

- Before 2008, the plaintiff has never received any summons, court order, a photocopy of the Minister’s certificate, or a Schedule II from any ministry or government authority; not

even a phone call from an agent or office of the Crown Defendants.

- On or about July 24, 2007, the plaintiff sent a letter to the Hon. Minister Diane Finley. On or about August 3, 2007, T. Gillies (Ministerial Enquiries Division) replied it, adding

that as the case was currently before the IAD, it would be inappropriate to discuss the matter further.

- In or before November 2007, the Revenue Services of BC or RSBC (Victoria, BC) sent a letter to the plaintiff, claiming that he had been indebted

to BC for $38,149.45 for his Sponsorship Default Program.

- The plaintiff did not have any sponsorship- or other debt-related contract or agreement with any, federal or provincial, ministry or government in all material times. Despite of this, the Government

of BC, in 2007 and/or 2008, originally demanded from him $38,149.45 in one payment without proper or legally acceptable explanation.

- The plaintiff, in 2007 or 2008, contacted the Ministry of Housing and Social Services of BC and offered to them

to start paying his alleged debt, without formally acknowledging a debt, in the same framework – the same number of payments over the same period – as it had been granted to Mr. Tieu, a Vietnamese that owed more than $101,000 to the Province of

BC due an irresponsible failure to support his sponsored parents. On the behalf of British Columbia, Ms. Penelope Lipsack as Counsel was the Crown’s representative in the matters with the plaintiff till about December 14, 2008 (the date of her last letter

to Z.A. Simon). Ms. Lipsack refused to accept the settlement offer of the plaintiff and did not propose a counter-offer or an alternative payment plan. Thus, since the plaintiff was unable to pay about $30,000 in one payment, no more negotiation has taken

place. (In 2009, the plaintiff sued Ms. Lipsack in her personal capacity at a Court in Victoria but he, obviously, could not succeed that way. His Writ of Summons was dismissed in 2009. The File Number was C090244.)

- In 2007 or early 2008, the RSBC

or another authority sent him a consent form to be signed by Ms. Reyes, instructing the plaintiff to contact her and returned the signed form to them. However, the plaintiff was unable to contact her. It seemed strange for the plaintiff: If those

social benefit payments to Ms. Reyes constituted his debt – and not the debt of Ms. Reyes – why was not he allowed to learn the amount of his alleged debt from the Crown?

- After almost eight years of complete silence following

the default, the provincial and federal authorities together began to garnishee his federal tax account, without any hearing or documentation, only acting on the RSBC’s request as follow. (His RSBC account No. is X11000006724.)

- On or about June

2, 2008, the B.C. Ministry of Housing and Social Services or the RSBC, without colour of right, sought and obtained funds from the tax account of the plaintiff, by conversion. The actual conversion took place in the CRA. The CRA intended to keep garnishee

the plaintiff’s funds in the amount of $38,149.45 plus a high compound interest that was not mentioned in any agreement signed by the plaintiff. The plaintiff thought that the CRA owed him a duty of care just like a chartered bank. The plaintiff relied

to his detriment on the CRA as an agency that knew and obeyed the laws of Canada. The plaintiff relied on the paragraph of the Sponsorship Agreement with Ms. Reyes that the Crown may take moneys from a sponsor due to a default or breach of the agreement only

within “an action in a court of law” and that “The suit may be placed in any court in Canada having jurisdiction over claims against the Sponsor (or Co-signer) for breach of contract.”

- Thus, in 2008 and 2009, Crown servants

of the federal CRA wrongfully, knowingly, by tortuous conduct, released funds or monies from the 2007 and 2008 tax credits of the plaintiff for the Revenue Services of British Columbia (“RSBC” below).

- On or about June 17, 2008, the plaintiff

received a photocopy of his Income Tax Return Information from the CRA. The date of the assessment was June 2, 2008 for the tax year 2007. It indicated a refund or credit of $3,577.83 but he has never received any refund. It simply disappeared. Much later

he learned that, out of that amount, $136.15 had been taken as GST while $3,441.68 had been recovered by the (BC) Sponsorship Default Recovery program.

- After the garnishment of his tax account, between June 19 and June 27, 2008, the plaintiff

received a letter from the RSBC with a Financial Report form. The letter referred an outstanding obligation for $29,417.04 that the plaintiff did not understand: there was a discrepancy of several thousand dollars in the arithmetic. Also, the fact that the

form was received a few weeks after the garnishment had revealed the bad faith of the RSBC officers. Thus, the plaintiff had no opportunity to complain before the garnishment.

- On or about July 10, 2008, the plaintiff sent a very long and

detailed letter to the Revenue Services of British Columbia in Victoria, BC. (He attached his Financial Report form completed, signed as on June 8 that should correctly read July 8.) His letter contained many legal arguments, some of them about his violated

Charter rights. In the letter the plaintiff denied his debt to BC but claimed that the claim against him was illegal and unconstitutional. However, he authorized the Canada Revenue Agency to confirm his circumstances toward the RSBC. The plaintiff

has never acknowledged his “debt” and did not make any repetitive payments so he is not a confirmed or judgment debtor.

- On or about August 5, 2008, the plaintiff sent a long letter to the Canada Revenue Agency, Attention: Mr. Bill Baker,

Deputy Commissioner in Ottawa. Its subject was “Assistance requested in a legal and accounting controversy.”

- On or about August 18, 2008, the plaintiff received a letter from the Canada Revenue Agency, signed by Patrick Bélanger.

It promised that his concerns will be given careful consideration.

- On or about August 20, 2008, the plaintiff sent a letter to the Hon. Rob Nicholson, then Minister of Justice. He has not received a reply to it.

- On or about September 3, 2008,

the plaintiff sent a letter to the Hon. Claude Richmond, Minister of British Columbia, or/and his two deputy ministers (Ms. Cairine MacDonald and Mr. Andrew Wharton), plus the RSBC. It contained an offer entitled “A proposed frame for settlement.”

He has not received any reply from them. About the same time (?), he sent a detailed letter to the Hon. Gordon Campbell, then Premier of BC, informing him about the torts and legal controversies.

- On or about September 22, 2008, the plaintiff requested

info from the Canada Border Services Agency regarding transit visa and return ticket requirements for his Chinese wife if she would spend a few months in Saint-Pierre et Miquelon (belonging to France) until her Canadian papers would be granted. He received

a reply, without any answer or suggestion.

- Between about September 30 and November 12, 2008, the plaintiff received a letter from the office of the Hon. Gordon O’Connor, then Minister of National Revenue, writing that the CRA was

unable to comment on his dispute with the Revenue Services of BC. The letter stated that the CRA and other federal and provincial government authorities have entered into an agreement to collect amounts owing. It added that the CRA did not determine who will

be identified for set-off action and a set-off action can only be suspended when the CRA is advised to do so by the originating department.

- Between September and November 12, 2008, the plaintiff began a correspondence with the Ombudsman BC office,

in which R. Brown (Complaints Analyst) and Judy Ashbourne were involved. Later the matter was concluded. They were unable or unwilling to solve any issues.

- On or about October 7, 2008, the plaintiff sent a letter of inquiry to the Ambassador of The

Netherlands in Ottawa, requesting advice about settling in that country or in its territories (in the Caribbean) in order to family unification since Canada’s red tape had not offered any solution.

- On or about October 24, 2008, he received a

letter from their Consulate in Vancouver, advising him that he could not apply for asylum before entering a country.

- On or about October 27, 2008, the plaintiff sent a letter to the Hon. Wally Oppal, Attorney General of BC, and to Ms. Penelope Lipsack,

Crown Counsel in Victoria, BC. A bit later he sent a photocopy of this letter to the IRB/IAD Registry as well.

- On or about November 4, 2008, the plaintiff sent a long letter to the Canada Revenue Agency’s Tax Centre in Winnipeg, requesting an

adjustment for the year 2007.

- On or about November 7, 2008, the plaintiff sent a letter to the Embassy of Spain in Ottawa. It was similar to the letter sent to the embassy mentioned above.

- On or about November 13, 2008, the plaintiff received

a letter from Sylvia Dalman (CRA in Burnaby-Surrey, BC) regarding his notice of objection received on July 31, 2008. She wrote that his objection was not valid.

- On or about December 23, 2008, the plaintiff had an airplane ticket from Calgary to Toronto,

in order to present his case at the IRB/IAD hearing. About twenty flights were cancelled in Calgary on that day, due to inclement weather. The plaintiff’s plane took off by a delay of 3.5 hours and arrived in Toronto with the same delay. He missed his

hearing by two hours, and lost about $800 in travel costs for nothing. In the IAD Registry, he wrote and filed a request for a new hearing. The Registry granted him a new hearing in its letter dated on or about December 24, 2008.

- On or around January

12, 2009, the Hon. Jean-Pierre Blackburn (then Minister of National Revenue) sent a letter to the plaintiff.

- On or around February 26, 2009, the plaintiff received an e-mail message from the CIC – Ministerial Enquiries Division. [He assumed

that it was sent by the Hon. Jason Kenney since it had followed his earlier letter sent to that Minister.] The title of the message was, “Your Wife's Application Status / Structure of the Immigration and Refugee Board.” It said, “…your

comments regarding the harmonization of federal and provincial laws with regard to immigration have been duly noted.”

- On or about March 15, 2009, the plaintiff wrote a letter to Canada’s Ambassador in Rome (Mr. A. Himelfarb), regarding

“Request for info about official procedures of immigration or political asylum” [for a Canadian citizen in order to settle in Italy]. He has not got a reply.

- On or about May 15, 2009, the plaintiff sent a letter to the Hon. Minister Diane

Finley regarding his concern about garnishing his future pension benefits if he needed to settle abroad. He has not received a reply. A copy of the letter was sent to Prime Minister Stephen Harper as well but the plaintiff has not received any reply.

- On or about May 27, 2009, the plaintiff filed an application for leave and judicial review to the Federal Court for an Order of Mandamus to require the IAD to issue a decision in this appeal. A Notice of Appearance was filed on June 4, 2009. On or about

on September 16, 2009, the Court dismissed the case.

- On or about June 4, 2009, the B.C. Ministry of Housing and Social Services or the RSBC, without colour of right, sought and obtained funds from the tax account of the plaintiff, by conversion. The

CRA transferred the $100.43 credit balance of the plaintiff’s personal tax account to the (BC) Sponsorship Default Recovery program, apparently to the RSBC.

- Or on about July 8, 2009, the plaintiff received a letter from Service Canada, signed

by Sharon Shanks. The letter threatened the plaintiff (and apparently tried to coerce him to pay) by claiming that a creditor “may obtain a garnishee summons without proceeding to court.” That principle was false and violated ss. 67.

(a) of the Financial Administration Act, R.S.C., 1985 because Crown debts (like the future CPP pension benefits of the plaintiff) were not assignable.

- On or about August 7, 2009, the plaintiff received another letter from the Hon. Jean-Pierre

Blackburn, Minister of National Revenue, regarding the set-off action on his income tax account. Mr. Blackburn considered the plaintiff’s matter with the CRA closed.

- On or about August 13, 2009, the plaintiff participated in a hearing by the

IAD/IRB in Calgary by videoconference. See Simon v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration),2009 CanLII 85533 (CA IRB). The IAD File Number was VA9-00194, with Client ID No. 2092-5897.

- Between October 23 and 27, 2009 the plaintiff filed and

served his statement of claim with the Writ of Summons, at the Supreme Court of BC (Vancouver), under the case number S097926. Neither of the two Crown defendants has submitted a Notice of Appearance by January 30, 2010 although (on or about November 19, 2009),

Mr. Peter Bell, Counsel to the Government of Canada sent him a letter regarding it. The plaintiff made a minor mistake in the style of cause, showing Deputy Attorney General instead of Attorney General. The Registry was unwilling to correct it, or, to give

direction. Therefore, the plaintiff served and filed an updated pleading inquiring about the status of the proceedings on January 30, 2010.

- On or about November 17, 2009, the IAD made a decision in which the plaintiff’s appeal was dismissed.

One can see the Crown’s strategy from the dates. In order to gain time, the Crown kept pressuring the IAD and the IRB to delay the matters and decisions related to Z.A. Simon and Ms. Zhong as a punishment of the plaintiff for his 2007 court case (FC).

From May 2007 to November 2009 approximately two and a half years passed in a limbo on Canada’s behalf.

- Before the end of 2009, the plaintiff applied for judicial review at the Federal Court to revise the IAD decision. His application for leave

and judicial review was dismissed. Pursuant to ss. 72. (2) (e) of the IRPA, “no appeal lies from the decision of the Court with respect to the application or with respect to an interlocutory judgment.” This

paragraph seems unconstitutional. It should perhaps add, “…in cases where national security is involved, except questions of debts or pure questions of law.”

- On or about January 8, 2010, the Government of Canada (Ministry

of Finance, Winnipeg) sent a notice to the plaintiff regarding his [alleged] outstanding debt. He received similar statements regularly.

- On or about January 26, 2010, the plaintiff sent a belated reply to the letter of Sylvia Dalman at the CRA (Burnaby-Surrey,

BC). He requested to learn the CRA’s position regarding the next legal step.

- On or about February 3, 2010, the plaintiff received a brief letter from the Canada Revenue Agency (Appeal Division in Surrey BC), signed by Sylvia Dalman, stating

that the CRA had no jurisdiction concerning the Citizenship and Immigration Canada sponsorship program and any indebtedness that may arise from a sponsorship agreement.

- On or about February 22, 2010, the plaintiff sent a letter from China to Peter