|

|

|

|

|

THE END OF CANADA'S DEMOCRACY

THE SILENCE OF THE CANADIAN JUDGES: THE END OF A DEMOCRACY

CRISIS OF POWER IN CANADA Canadian immigration law and the fall of a democracy: the policies dominate

by Zoltan Andrew Simon* (historian, amateur scholar) E-mail: zasimon@hotmail.com Twitter: @ZoltanAndrew Abstract: This paper contains the results of six years

of legal research. It deals with the controversies between Canada’s laws and immigration policies. After examining the numerous unlawful elements in the treatment of the family class sponsors, it concludes that the same trend is valid for Canadian democracy.

The transition to a totalitarian regime happens by reducing the powers of Parliament and the judges while the ministers’ unlawful policies grant excessive power to the administrators and registries. The conclusion of the paper reveals the crisis

of leadership in Canada, including the apparent corruption in the federal government and the federal court system. A short form of this academic paper has been sent to many Canadian columnists and Calgary lawyers in November 2013, under the title “Crisis

of power in Canada.” Some say that judges hate hypothetical cases in pleadings. That may be a myth, so we start with such an example. The law is like a mathematical equation: it still must work if you use extreme facts and situations.

Keywords and abbreviations: agreement, British Columbia (BC), Canada Revenue Agency (CRA), Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (“Charter”), conspiracy, constitutional questions, contract,

debt claim, debt provable, Federal Court (FC), Federal Court of Appeal (FCA), garnishee, “hermaphroditic” litigant, Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA), limitation period, ministerial certificate, Ministry of Citizenship

and Immigration Canada (CIC), money extortion scheme, sponsorship debt, Supreme Court Act, Supreme Court of Canada (SCC). *Address correspondence to the author at 6 Rutherford Drive, Red Deer, Alberta, Canada T4P3G9. Fax: (403)

341-3300; E-mail: zasimon@hotmail.com URL: www.correctingworldhistory.com INTRODUCTION Family class sponsorship

is common in Canada. Although most cases are different, the federal policies allow any ministry to take advantage of the re-victimized sponsors illegally. The following hypothetical case illustrates this social problem. IMMIGRATION

TO CANADA: Heaven or hell for sponsored family members Celine Doe immigrated to Canada in 1986. She met the handsome Fred in one of the ex-colonies. He was the son of a tribal chief. He spoke both English and French quite well. Celine thought

that he could become an asset both for her and Canada. Fred promised to marry her (but he never did). She sponsored Fred who arrived in Canada in 1990 with his daughters. Soon he changed, started to abuse her and moved out. Celine was left with Fred’s

two daughters that were 17 years old and ten months old. She took good care of the girls and supported them. A year later a criminal kidnapped the baby Lisa. The local police could not locate them. Then Celine got a phone call from Fred who was studying at

a university. He wanted to become a judge and said he had no money. In reality, Fred applied for social benefits in 1990. He reported to the administrators that his wife had abused him. When they asked for details, he lied, “She told me that she

hated me because my skin was too dark.” He also claimed that his two daughters were living with him and he was supporting them. The manager pacified him by stating, “You are now in a democratic country where no one can discriminate against you

because of your race or ethnicity. We guarantee that you can study and choose a good profession.” The office granted him social benefits and sent him to a university. Celine did not suspect anything, since no government official had contacted her. Fred

kept moving from province to province and applied for – and received – social benefits everywhere. (Fred often received large amounts of money at Western Union sent by his secretary in his old country. Canada had no idea about that. He lived with

several rich women as a playboy then dropped out of the university, due to his drinking problems.) In the meantime, Celine realized that she had been waiting for the return of her beloved Fred in vain. Fred’s older daughter was working non-stop

from 1990 to 1998. Then she had an accident in the factory and lost her right hand. Celine had to support her. In 2008 Celine tried to sponsor an old friend from Europe who was interested in marrying her. The CIC was silent. In 2010 she received a letter stating

that they were investigating her debts; she could not sponsor her new man. Even his visitors’ visa was refused. Back in 1993, the RCMP found Lisa but they were unaware of Celine as her legitimate guardian so she was given to another couple. Five

years later the police received information about Celine but did not want to create a legal dispute. They informed the ministry of human resources and families. The provincial ministry immediately found out the truth but maliciously decided not to inform Celine.

A car hit Lisa in 2005 and the ministry paid the high costs of his hospitalization till she died at age of 24. This was the strategic moment for the administrators to send a statement to Celine. It said that unfortunately Lisa was dead, but Celine owed

the province over $1,300.000 – due to a default of her sponsorship obligations. (Since the province charged a compound interest of 6% till 2013, the ministry expected a better return by delaying her notification.) In 2013 Celine received more

surprise letters. The statements showed that she owed another debt of $800,000 to the governments, due to the social benefits paid to Fred from 1990 to 2000 in eight provinces. They threatened her that they half of her salary would be garnisheed if she did

not pay her debts. The oppressed but shy and frail Celine filed a statement of claim at the courts. The provincial court sent her to the federal court while the federal court sent her to the provincial court, both qualifying her as a vexatious litigant.

Her tax account has always been garnisheed. She wanted to visit her fiancée but she could not afford it. She had no free time, working day and night for nothing, for the errors of the administrators. When she considered settling abroad, a manager

of Service Canada sent her a letter which said that her future pension benefits may be garnisheed without any procedure at the courts. Celine’s lawyer explained to her that the word “may” in the ministries means that her pension

benefits shall be reduced, perhaps to zero. He showed Celine the Canada (Attorney General) v. Mavi, 2011 case as a rule for such interpretation. Celine would be better off abroad as a political refugee, revoking her citizenship to

protest. Here – in “the most livable country of the world” – she could only commit suicide, or turn into terrorist by burning down a government office to ashes. She could start a public hunger strike and notify the international media,

or even handcuff her wrist and ankles to the steel fence of Parliament Hill on Canada Day. She cannot expect any help from the champions of red tape. THE TORT ISSUES TROUGH CONSTITUTIONAL QUESTIONS During his nine

court cases (2007-2013) the author submitted the above test situation with 28 constitutional questions to the FC, FCA, and the SCC recently. The judges remained silent. Most of them held that they had no jurisdiction just because the recovery of the sponsorship

“debt” was originally requested by a province, even if the federal CRA did the actual garnishment. Other judges found that pleadings without a claim for damages – only for restitution of moneys and declaratory relief – were unusual

and unacceptable. Similar circumstances and questions may occur in any country, particularly where federal and provincial laws coexist. The basic dilemma is whether federal public servants need to observe the federal laws only

while provincial employees should observe only the provincial laws. This question is often raised in garnishment law. Namely, what authority is responsible for observing the legislation if a province wants to garnishee unlawfully a firm or a person? If

a province wants to proceed with the garnishment without any legal basis – like a ministerial certificate filed at a court – but the federal state allows such unlawful garnishment and puts it into practice, which one should bear the legal

burden for the damages in tort? In general, on which side is the guilt and the legal responsibility in such improper garnishment cases in any country? Which side needs to verify that the debt is “provable” or only a baseless claim? The provincial

authorities would answer that it is not punishable to ask a higher authority to start an illegal garnishment. They are just requesting the state to do something illegal. Canada has the responsibility of complying with the federal legislation regarding garnishment,

they would say. The federal authorities claim that the responsibility lies with the provincial government that requested the garnishment. Thus, the provincial and federal governments are blaming each other for such tort situations. The innocently suffering

firms or individuals are facing insurmountable difficulties and uphill battles at the courts against the joint tortfeasors commonly called “red tape.” Who is guilty in any tort, generally speaking, if a party requests another party

to do something unlawfully, or commit a crime? Are they joint tortfeasors? If one of the parties is innocent in the money extortion scheme, which one is that? This conflicting picture may remind us to a military airplane that is flying upside down.

Such situations do happen in real life sometimes. The pilots do not trust the instruments, only their own confused senses. The senior pilot thinks that the junior pilot is controlling the plane while the junior believes that the first pilot

controls everything. The result is the crashing of the airplane. In our case, the instruments and gauges of the plane correspond to the legislation. THE SILENCE OF THE JUDGES (CANADA)

Let us return to the twenty-eight constitutional questions that have been before eleven federal judges. None of them was able – or allowed – to answer any of the following 28 questions: - Does an extreme interpretation of ss.

145.(3) of IRPA (Assented to 2001-11-01) and s. 5.23 of a federal policy named “IP 2”, resulting in a new punishment by inserting the words “at any time” (also beyond the prescribed

limitation period, till the death of the sponsor) violate the rights in s. 8. [unreasonable seizure] and 11.(b) of the Charter, s. 32. of the Crown Liability and Proceedings Act, subsections

39. (1) and (2) of the Federal Courts Act, s. 134. of IRPA, subsections 3.(5) and 9.(1) of the Limitation Act (of British Columbia), and attack collaterally the

Court’s order set out in Markevich v. Canada, 2003 SCC 9, [2003] 1 S.C.R. 94, Sherman v. The Queen, 2008 TCC 487, Bentley v. Canada (Employment Insurance Commission), 2000 CanLII 15758 (F.C.), where a former Act governed,

and Hupe et al. v. Government of Manitoba, 2007 MBQB 195, at least for sponsors that signed their CIC forms before June 2002? [In our case and in Markevich v. Canada (supra), Canada was “agent of the Province.”]

- Is it possible that in the category of “other than tax” debts – including student loans, pursuant to ss. 16.1(1) and 16.2(1) of the Canada Student Financial Assistance Act, ss. 18.(2)

of the Canada Student Loans Act, and in cases related to rent – the legally prescribed limitation period applies everywhere except for alleged sponsorship debts where the self-help action or the Minister’s certification of debt may legally

take place after several decades of silence?

- Shall the meaning of “debt” in s. 145.(3) of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act include any uncertified debt claim or “alleged debt”?

- Shall

the word “recover” in s. 145.(3) of IRPA include automatic garnishment without any previous contract between the sponsor and any federal or provincial ministry, without the involvement of any court, and without sending

any garnishee summons, similar documents or court order to the alleged debtor before garnishment?

- If both answers to questions 3 and 4 are affirmative, shall ss. 145.(3) of IRPA vitiate subsections 11.(a)

and (g) of the Charter as Part I of the Constitution Act (1982), subsection 146.(1)(b) of IRPA, sections 12. and 15.(2)(a) of the Interpretation Act,

s. 118.(2) of the old Immigration Act, ss. 449.(1)(b) and (2) of the Federal Courts Rules, s. 27. of the Garnishment, Attachment and Pension Diversion Act, sections 32.,

45. and 52. of the Family Orders and Agreements Enforcement Assistance Act, ss. 135.(b) of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations, s. 9. and Schedule

II of the Family Support Orders and Agreements Garnishment Regulations, ss. 76.(1)(b) of the Financial Administration Act, and ss. 42.(1) of the Canada Revenue Agency Act, at least in cases

of sponsors that signed their CIC sponsorship agreement or undertaking forms before 2002? [Subsection 118.(2) of the Immigration Act goes, “Any payment of a prescribed nature… may be recovered… in any court of

competent jurisdiction as a debt due to Her Majesty in right of Canada…”]

- Should the answers to questions 3 and 4 be affirmative, is ss. 145.(3) of IRPA of no force or effect because it contravenes subsections

15.(1) and 52.(1) of the Charter?

- Since here the sponsorship agreement obligation is a liability not arising out of trust or contract – only an agreement between two persons – and judgment has

not been recovered on it, does the federal policy that ignores the formal requirements prescribed by federal and provincial laws regarding garnishment or attachment also violate s. 3.(1) the Court Order Enforcement Act [RSBC 1996]?

- If the CIC forms promise three different things to three groups – the sponsors, the sponsored persons, and the provinces – and contain fatal contradictions, claiming in paragraph 9 of the Sponsorship Agreement that “The Sponsor’s

(and Co-signer’s) obligation is limited to providing for the shortfall only” while paragraph 11 claims that the same obligation is at least 100%, can it be assumed that the sponsors as reasonable persons have understood the essence of those sponsorship

documents and the entrapments in them?

- If such rigid interpretation of a gentlemen’s agreement (paragraph 11. of the CIC Sponsorship Agreement form, “It is further agreed that damages will not be less than the total of all amounts

actually received by the immigrant…”) and the words “the sponsor is considered to be in default” in the federal CIC-CRA policy named MOU (Memorandum of Understanding) always result in an absolute and unconditional 100% financial

responsibility of each sponsor while promises 0% responsibility for every sponsored person and public servant, is it an assumption by prejudice that Canadians – the sponsors – are always guilty and accountable in every default while aliens and

public servants are always innocent and not accountable for their actions? Would such baseless prejudice, stereotyping and discriminative approach satisfy the tests cited at [70] of R. v. Oakes, [1986] 1 SCR 103 and Andrews v. Law Society of British

Columbia, [1989] 1 SCR 143 and constitute an infringement on s. 15.(1) of the Charter, thus rendering those CIC forms invalid? The sponsors’ already disadvantaged position within Canadian society resulting in substantively

differential treatment between the sponsors – as a group of Canadians by nationality and residence – and the aliens (that are always non-Canadians by nationality and residence when they apply and receive the promises of Canada), unjustly shifting

the whole burden to the sponsors by avoiding the courts.

- Similarly to question 9, if such misinterpretations are acceptable in the policies, so the requirement for a summons at a Court or filing the Minister’s certification for a debt is skipped

in practice, could that undermine pages 684-691 of Donohoe v. Hull, 24 SCR 683 and vitiate the following sentence in the sponsor’s CIC “Undertaking” form: “The Minister has a right of legal action in a court of law

for the debt against the Sponsor alone, the Sponsor’s spouse (if Co-signer) or against both of them,” contradicting paragraphs 11. and 18. of the Sponsorship Agreement? [Regarding the sponsored person’s “action in a court of

law against the Sponsor” where the Crown may only represent the sponsored person. The legal action, just like at paragraph 27 in Canada v. Mavi, does not guarantee success.]

- Does the words “the Minister” in ss.

146.(1) refer to (a) the federal minister in the Cabinet or Privy Council responsible for the administration of the same Act or a related field; (b) to any minister of any province or country; (c) a minister of a church to which the

sponsor or the sponsored person belongs?

- Could a vague sentence about an unspecified future punishment in the same CIC “Undertaking” form claiming that “The Minister may take other actions to recover the debt

from the Sponsor or the Sponsor’s spouse (if Co-Signer)” include “other, illegal actions” and render any “Undertaking” void ab initio?

- Similarly to question 9, if such misinterpretation governs

– assuming a collective guilt or offence of every sponsor in the federal forms and policies in cases when the sponsored persons unnecessarily apply for social benefits – and leaves only one secure prevention for the sponsors, namely to subject

the new immigrants to forcible confinement, violating subsections 279.(2), 279.01(1) and 279.011(2) of the Criminal Code RSC 1985 and seriously offending law and public policy, would such fatal error

render those CIC agreements null and void?

- Can the absence of any reference in the federal legislation to the ability or necessity of the provincial governments to sign contracts with the sponsors – in the days when the sponsored

persons apply for or receive social benefits – be interpreted that Parliament had prohibited for the provinces to sign such contracts?

- Can any party claim for damages in connection with a sponsorship undertaking if the party has not been a signatory

to any related contract, and so undermine the Court’s decision in Bilson et al. v. Kokotow et al., 23 O.R. (2d) [1978]?

- Can any provincial or federal ministry treat new sponsored immigrants as permanent residents differently than other

Canadian citizens and landed immigrants when applying for free social benefits – by turning those free universal benefits (including tuition or medical benefits, or compensations for injuries at work) into “sponsorship debts” that often remain

in their families as debt burdens and punishment – without violating ss. 15.(1) of the Charter?

- Does an assumption based on stereotyping and prejudice – that Canadian citizens or permanent residents, after having

been in the work force only for two years, are not a burden for the society and cannot cause damages for a province through social or medical benefits, while family class immigrants sponsored by them constitute a burden for the society, causing damages after

nine years of hard work, applying for such benefits in the tenth year – undermine ss. 15.(1) of the Charter so it is invalid? [In the former Immigration Act, R.S.C. 1985, the requirement to support the sponsored immigrants

in the family class was ten years but in IRPA only three years.]

- Where the direct consequence of the arbitrary extrapolations and misrepresentation of the legislation in the policies results in a long forceful separation of innocent families

(for five years or more), constituting cruel and unusual treatment or punishment without reasonable explanation, have their rights under sections 7 and 12 of the Charter been infringed?

- If the CIC sponsorship

forms fail to specify whether a Minister is party or signatory to the agreements or not, fail to disclose material facts – that the Ministers’ plan is to disregard the federal limitation, contract and garnishment laws of Canada and the Charter

in their policies and in practice – and mislead the sponsors by the false promise of a lawful court procedure in case of defaults, also offer an impracticable severability clause through a non-existing court while not specifying any amount or interest

rate on the debt, can it be reasonably concluded that – despite of these crucial legal errors going to the heart of the agreements – “a meeting of the minds” or be ad idem existed between the sponsors and any Minister, so the

signatures of the sponsors are always valid, and their personal agreements can be handled as valid contracts with a Minister?

- Is it justifiable to claim in a federal policy (paragraph 5.18 of the “IP 2”) that a “binding

contract” exists between the sponsors and the Minister of CIC, in order to mislead every civil servant, allowing them to do automatic garnishments without court procedures, so the contradicting IP 2 shall override ss. 132.(4)(a)

to (c) of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations? [The latter only specifies statements and declarations, not contracts. Several laws allow such garnishment based on contracts but not agreements.]

- Since the rights and obligations

of the sponsors changed radically in 2001 by the introduction of IRPA and the federal ministries ignore the fact that the earlier sponsorship agreements were signed under the former Immigration Act (that respected the limitation and garnishment

laws through the involvement the courts), is it possible to claim – in light of Toronto-Dominion Bank v. Duffet, 2004 NLSCTD 30 or Bank of Nova Scotia v. Antoine, 1998 CanLII 14918 (ON SC) – that each sponsorship agreement and

undertaking signed on CIC forms before June 2002 (when IRPA came into force) has become a “frustrated agreement” that is null and void?

- If the former Immigration Act is determinative and applicable for such agreements

signed before 2001, and section 4.(3) of its Immigration Regulations, 1978 is applicable in such cases, could the exclusion of the disqualified sponsored spouses mean that their sponsors are not sponsors in the family class from the

legal point of view and, therefore, a non-sponsor could not have any sponsorship debt, so the debt belongs to the disqualified spouse? [Section 4.(3) states, “The family class does not include a spouse who entered into the marriage primarily

for the purpose of gaining admission to Canada as a member of the family class and not with the intention or residing permanently with the other spouse.”]

- If the answer is positive to the previous question – in order to interpret the minimum

period for which a sponsored spouse should have resided “permanently” with the sponsor – does ss. 5.(1) of the Immigration Regulations, 1978 offer a guideline as “1 year”?

- Was the intention of Parliament to prohibit the Federal Court dealing with the severability issues of the CIC Sponsorship Agreement and Undertaking forms, by granting such jurisdiction only for the provincial courts to severe the invalid

and illegal terms of those federal forms related to immigration, a strictly federal jurisdiction?

- If arbitrary and capricious interpretation of the legislation by the policies is allowed, can they vitiate the constitutional applicability of ss. 23.(2.1)

of the Financial Administration Act, or s. 26. of the Family Orders and Agreements Enforcement Assistance Act?

- If the sponsorship and undertaking documents on the CIC forms do not explain the term “not self-supporting”

and are silent about common situations where the sponsored persons simply want to become independent from their sponsors, or, when the province unilaterally removes them from the work force by sending them to schools for years, can those gaps in the agreements

be arbitrarily filled by the administrators at the expense of the sponsors?

- If persons are usually not responsible for the unexpected actions of their dogs which are their properties, can the same persons be held fully liable for the unpredictable

actions and debts created by their spouses – that are not their properties but totally independent legal persons – and can a vague Canadian legislation change this principle to undermine universal jurisprudence that worked well for thirty-eight

centuries since the laws of Hammurabi?

- If the sponsorship obligations are equally valid to every sponsor, is it possible that in cases like this one – where Canada sponsored a Convention refugee who received some welfare benefits in the decade

after his landing –, may a province recover such “debts” from Canada forever, without a certificate of a Minister or court procedures, only by administrative set-offs?

FACTUAL BACKGOUND AND THE PLEADINGS

The author was born in Hungary, in 1949. He fled to Canada in 1976 when it was still a free and democratic country. In 1999, he sponsored a woman who – six months after her landing – wanted to become independent so they divorced. She

found a wealthier man while BC paid her welfare for five years by mistake. Then she accepted the first job offered her by BC’s administrators. The author remarried in China in 2006 but the Crown refused to grant any visa for his wife and her student

son. Alberta’s workforce would need both of them but Canada’s tort prevails. The federal government had failed to instruct the visa officer about the applicable limitation period and the related federal and provincial legislation. [Pursuant to

rule 135.(a) of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations, the “default” of his previous sponsorship undertaking took place in October 2000.] The Immigration and Refugee Board’s Immigration Appeal Division

held that the visa officer had not made any mistake. An appeal to the Federal Court was dismissed. The immigration aspect has been closed, pursuant to subsection 72.(2)(e) of IRPA. Such forceful separation of innocent families constitutes

a cruel punishment. It also causes economic losses for Canada. Instead of getting needed immigrants, part of the sponsors’ money is spent abroad. As another punishment, the federal CRA started to garnishee his tax account in 2008, beyond the limitation

period of six years, by illegal and unconstitutional means without colour of law, by conspiracy, misrepresentation of the laws of Canada, breach of trust and wrongful conversion. Finally, Service Canada informed him that they may garnishee his future pension

benefits without any court proceeding, due to his alleged debts. If he moves abroad, he would lose his old age benefits and supplements as well. His questions were related to contract, garnishment, and limitation laws and the irreconcilable controversies

between the will of Canada’s Parliament with the contradicting policies of the federal ministries. (About thirty-five paragraphs of Canada’s laws have been contravened.) His last court cases were related to a federal money extortion scheme and

the unconstitutional garnishment of the family class sponsors without the courts’ involvement and without filing a ministerial certificate about their alleged debts. The Province of BC officially admitted in writing that no such certificate had existed

in his case. When he learnt this fact, it meant exceedingly rare circumstances. Since the SCC’s Registrar could not see such rare circumstances, it means that probably thousands of Canadian families suffer the same fate. The author – as

plaintiff – fell in a trap at the beginning of the pleadings in 2012. Although the only defendant was HMTQ (Her Majesty the Queen), two defense counsel sprang up. One represented the Crown and another counsel the Registrar (the “SCC Party”).

Such trick – forcing him to fight two parties – tried to ruin him financially and mentally. On 5 July 2012, he tendered an Amended Statement of Claim for filing. Mr. Prothonotary Lafrenière, in his directions, instructed the Registry to

reject it, based on Bruce v. John Northway & Sons Ltd., [1962] OWN. 150. The Federal Court Rules allow the appeal of an order of a Prothonotary but it is silent about appealing his direction. (A Registrar would refer to such silence and

refuse its filing.) The writer was planning to discontinue his pleadings when unexpectedly received a double court order. Section 34.(1) of the Federal Court Rules goes, “General sittings of the Federal Court for

the hearing of motions shall be held, except during the Christmas or summer recess...” A sitting of the FC is the same as the sitting of a judge. Thus, it was hard to believe that the judge delivered her two orders on 20 July 2012 while she was

standing. One order was regarding the Crown, another one about the person that approved the SCC’s [tortious] website http://www.scc-csc.gc.ca/ar-lr/gl-ld/gl-ld-eng.asp#I. That person

turned out to be the Registrar of the SCC, so apparently the silly plaintiff had sued the SCC – through one of its members with absolute immunity – at the Federal Court. Since the author’s last appeal, the said website – with the Rules

and the Act – has been removed, only the http://www.scc-csc.gc.ca remained. In the orders, Madame Justice Tremblay-Lamer concluded that a possible future administrative decision or allegations regarding hypothetical decisions

did not disclose a reasonable cause of action so the action cannot succeed. (Recently, it seems, the Crown caused her orders removed from the www.canlii.org website.) In R. v. McCraw, [1991] 3 SCR 72, the appellant wrote to three cheerleaders,

“…even if I have to rape you.” The Court held that it had been a threat to cause serious bodily harm. Mr. McCraw’s possible future decision was punishable which fact contradicts Madame Justice’s reasoning above. As

for the tortious silence of Service Canada or a Minister, it is comparable to Longley v. Canada (Minister of National Revenue), 1999 CanLII 5750 (BC SC). The Crown remained silent about a tax loophole. The Court awarded $55,000 to Mr. Longley

in damages. Let us illuminate such tortious silence by a hypothetical situation. Say, two ministers decide to spend their vacations in Hawaii with their husbands, parents and children. They buy the tickets from Canadair in January for their flights

in August. They send a letter to Canadair requesting details about the safety policies. The general manager replies them in January, “…In case of emergency, the pilot may order the passengers to throw out excess weight. Persons over 65 and girls

under the age of 10 belong to that category.” The ladies urge the company to explain such unlawful policy. The management remains silent. In July, the ministers buy new tickets from Korean Air and sue Canadair for tort. The latter firm pleads innocent

while they resell the seats for others. Have the ministers breached their contracts with Canadair? Are they bound to lose at the Court because they cannot sue a possible future administrative decision of the pilot? A reasonable person would

strongly disagree. The first difficulties originated by the improper refusal of the plaintiff’s Reply for filing. The Registry deemed the date of the Purolator driver’s delivery to a post office as the date of service on the

plaintiff, although the documents were held by a postmaster during a weekend. The refusal has caused irreversible losses and prejudice for the appellant since the unfiled pleadings cannot be referred to anymore. An administrator’s menacing the plaintiff

added insult to the injury: she wrongfully claimed that the only solution for the Registry was either to shred his Reply, or, return its five copies by mail. Many weeks after the dismissal of the plaintiff’s document for filing, the Court admitted

that the document’s filing should have been accepted. Then further mistakes happened. Namely, the refusal of the Appeal Book’s filing, claiming that a Motion for Extension of Time had to be filed first since the rule regarding

Christmas recess days did not apply for the appellant. The volumes of his Memorandum were not accepted for filing because several documents or exhibits lacked signature and seal. (The administrator assumed that they belonged to an affidavit although

the affidavit clearly stated that it had no exhibits at all.) Later the Court concluded that it had been improper to deny the filing of both documents. The appellant has served and filed his Book of Authorities on February

15, 2013. He served his 4th Motion Record on 3 April 2013 when he found a package sent by the FCA Registry containing all the five sets of pages 37-60 of the Appeal Book. The cover letter falsely claimed that they were obeying

the 22 March 2013 Order of the Court by extracting those pages. By that act, the Registry’s aim was to destroy properly filed documents, in order to blind the judges of the FCA and the SCC, preventing them from seeing the full picture. The

said Order was silent about extraction of pages 37-60 and did not intend to violate s. 344.(1) (d) of the Rules by omitting a crucial document for good. It ordered that the Appeal Book had to be filed, without

saying, “except pages 37-60.” It emphasized that “the expeditious, fair, and efficient conduct of this appeal will not be served by returning these documents to Mr. Simon…” However, the administrator disobeyed the

Order and returned part of the documents by truncating and altering the Appeal Book without justification. The Judge only ordered that [pages 37-60] “are not to be referred to…” which referred to the parties. He did not prohibit

for the three judges of the FCA to take a second look at that issue. He added that “pages 37-60… are struck…” However, the Registry misinterpreted the word “struck.” Common law confirms that the words “struck”

or “strike/struck out” pages of a document do not mean “destruct,” “shred” or “return to the sender.” Krpan v. The Queen, 2006 TCC 595 and British Columbia (Civil Forfeiture) v. Vo, 2012

shows that if parts of a document were “struck out” there were crossed by horizontal lines. “Struck” does not mean that the parts of a document must be erased by eraser. The courts struck out thousands of claims but those documents

shall remain in the court files, not returned to the senders without a trace in the court system. The next issue was a procedural situation so far unknown in Canada. Rule 346.(2) of the Federal Courts Rules states, “Within

30 days after service of the appellant’s memorandum of fact and law, the respondent shall serve and file the respondent’s memorandum of fact and law.” The Respondent Crown physically received the appellant’s Memorandum on February 15,

2013. Thus, the appellant should have received the Crown Respondent’s Memorandum of Fact and Law by March 17, 2013. However, the Crown misunderstood the Rules and served its Memorandum on the appellant by a delay of thirty-three days: sixty-three

days after the service, instead of thirty. Rule 3 states, “These Rules shall be interpreted and applied so as to secure the just, most expeditious and least expensive determination of every proceeding on its merits.” Regardless these two

rules and Rule 72.(3), both the Registry and the Judge accepted the late filing of the respondent Crown’s Memorandum without hesitation. For comparison, in Abdessadok v. Canada (Canada Border Services Agency), 2006 FC 236, the

applicant misunderstood the Rules and exceeded the time limit by 24 hours. Therefore, his application was dismissed. The order of 30 May 2013, gave the following reason: “The Court has no cognizance of an appellant’s memorandum

until it is filed, and in that sense a respondent has nothing to respond to until the appellant’s memorandum is filed. It would be absurd to construe the Rules to require the Crown respondents to file their memorandum 30 days after it was served on them

(i.e. March 17, 2013) when the appellant’s memorandum had not been accepted for filing on that date.” An examination of the entire Rules sheds light on the legislative intent. Many paragraphs in these Rules reveal that

the expeditious proceedings were Parliament’s main consideration. Sometimes a party is losing millions of dollars per week. In every court case, the issues are between opposing parties. A party is not fighting against the Court or the Registry. Thus,

the parties shall communicate and serve each other in a timely manner at each procedural step. The timely service on the Registry is less important because the Court does not get involved before the actual hearing. Thus, the above order of Madam Justice was

patently unreasonable. The instant author appealed it on June 8, 2013. (At the same time, he requested the Court to interpret the direction of Mr. Justice Nadon, for its two paragraphs contradicted each other.) Earlier, on 27 March 2013, he served his Requisition

for Hearing on both Crown defendants. He had simply followed paragraph 347.(1) of the Federal Courts Rules. The Court should not penalize him by costs of $500 for obeying the law. The Rule goes, “Within 20 days after

service of the respondent’s memorandum of fact and law or 20 days after the expiration of the time for service of the respondent’s memorandum of fact and law, whichever is the earlier, an appellant shall serve and file a requisition in Form 347

requesting that a date be set for the hearing of the appeal.” The court, apparently Chief Justice Blais, remained silent. But what does silence mean? Silence after an appeal means unfinished business. (What would a judge do if a heart surgeon

would take a long vacation and leave the chest of the judge’s son or daughter open forever?) The next judge, ignoring the silence and the lack of a final judgment, treated the pending matters as a resolved one against the appellant. Thus, she ordered

the author to pay $1,000 immediately, qualifying his pleadings as vexatious. She did this although counsel had emphasized that the Crown had not applied to have the author declared a vexatious litigant. So far the appellant author had been denied of

his right for a fair hearing. However, the Federal Court of Appeal finally scheduled a hearing for the case: in the morning of 26 November 2013 in Calgary. If the judges would not remain silent again but finally would be able to make a decision the trial will

be a turning point in Canada’s history. Canadians could learn if the country would proceed further towards fascism based on abuse of power and extortion schemes, or, we may safely return to a free and democratic society. Canada looks like a great

and free country on the map, or, from a bird’s eye view. Birds include eagles and doves that fly freely sky high while surveying or supervising a country from ocean to ocean. Others are parrots that are sadly chirping with their wings trimmed, in a very

limited space, say, a cage in a basement. Those pets receive more bird food if they keep repeating the four-letter words of their owners. Our judges have more rights than birds do. It is the free choice of any judge to which category to belong. Mr.

Duplessis was Prime Minister and Attorney-General of Quebec half a decade ago. In Roncarelli v. Duplessis, [1959] SCR 121, the A.G. lost his case. Today, we believe, Mr. Roncarelli may not succeed against an A.G. at any court. The judge may conclude

that he does not have a scintilla of chance to win. However, judges could not write in their Reasons that “the plaintiff’s action could not succeed because every judge is biased in dictatorships.” The appellant author filed for bankruptcy

protection in March 2013 at BDO Canada Ltd. The excellent RBC Bank and Canada are his creditors, let alone BC’s $38,000 claim related to his alleged sponsorship debt. Following his desperate step, the Crown planned to eliminate him as an incompetent

party without any right. Canada wanted to dismiss his pleadings or claimed that it was permissible for a creditor to be both the plaintiff and defendant in the same action (the so-called “hermaphroditic litigant”). Section 38. of

the Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act was never intended to be used as a litigation tactic for short-circuiting the need to defend a valid cause of action. The law of bankruptcy does not recognize the right of a potential defendant (and creditor of the

bankrupt) to become both the plaintiff and the defendant in the same action. In Isabelle v. The Royal Bank of Canada, 2008 NBCA 69 the Bank persisted with its argument that the law fully accepted such concept, referring to R.M. Jackson

“The Hermaphroditic Litigant: Suing Yourself Under Section 38 of the BIA.” In Deloitte, Haskins & Sells Limited v. Graham, 1983, the judge wrote, “In any event, under the Alberta legislation there is no entitlement,

no right, but merely a hope that the court will exercise its discretion in favour of the applicant spouse.” Regarding “things in action” or “choses in action”, the judge added, “My conclusion is supported by the French version

of s. 2 of the Bankruptcy Act. There, the word ‘biens’ (which corresponds to ‘property’) is defined as including ‘droits incorporels’ (corresponding to ‘things in action’). It is clear that in French

what contemplated by that phrase is ‘rights’ and not merely a hope of favourable exercise of judicial discretion.” The Court held that the author’s pleadings were vexatious so it is clear that he had no “rights” in choses

in action. The trustee cannot take away a non-existing right from a bankrupt. Recently an interlocutory order of the Federal Court of Appeal dismissed the Crown’s motion to dismiss the author’s appeal because he had claimed damages for undue

influence and intentional infliction of mental suffering. Finally, two extremely interesting tort cases could be mentioned. In Young v. Bella, 2006 SCC 3, two professors assumed that a student was an abuser of children. They ruined

her career by their silly and ignorant attitudes. A jury awarded her $839,400 in damages. The other example is a huge conspiracy case that helped to change Brazil’s face. Over 380,000 documents and 857 persons – judges, politicians, bankers,

generals, etc. – have been involved. See Gosman (2000) and Stokland (2003). They smuggled the drugs by military helicopters. (José Carlos Gratz, ex-president of the legislative assembly in Vitória, was boss of the author’s girlfriend.

He often stated, “I am the law.” Finally, he tried to escape to overseas but he was arrested at the airport and ended up in jail for several years.) STREAMLINING CANADA – THE END OF A DEMOCRACY [The

real scene of this law research article is Canada but judges in other countries may face similar constitutional questions one day.] The alleged corruption issue of Canadian senator Mike Duffy is only a tip of the iceberg. It may be covered

up by a mat but an iceberg cannot be swept under that. I mean the present fragile state of Canada. A huge fault line is dividing the country: Parliament and Canada’s impartial judges on one side while some cabinet ministers and the federal public servants

on the other. (Every Canadian judge is independent: the majority from the government and the minority from justice.) The cabinet granted to its bureaucrats endless power, taken from Parliament and the SCC judges. The latter two suffered a “short circuit”

and gradually became redundant. Our top federal judges may be excellent but the nation’s problems simply cannot get before them. The ministers keep pressuring the court registries not to file pleadings that would expose their torts. Many Canadians

feel that most of their judges are corrupt and crazy that protect the criminals but ignore the safety of the public and the police. Such view is wrong. The real reason lays at a tortious website, “Representing Yourself in the Supreme Court of Canada.”

In it, the Registrar simply silences s. 61. of the Supreme Court Act that would allow appeals if errors in law are claimed at the lower courts. Instead, he is raising its s. 40.(1) and the Rules to exclusive

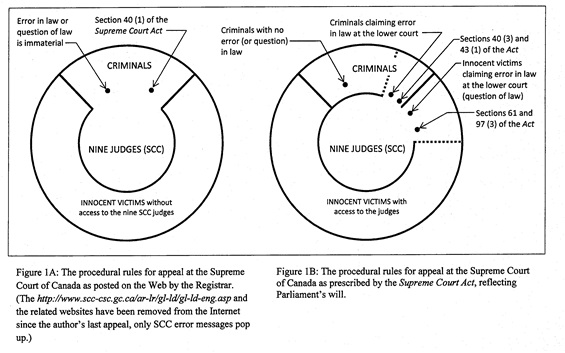

power. See Figure 1.

Figure 1 (1A and 1B) above demonstrates the great difference between Parliament's will and the opposite policy of the honourable white collar tortfeasors, represented by the Registrar of the Supreme Court of Canada.

Figure 1 (1A and 1B) above demonstrates the great difference between Parliament's will and the opposite policy of the honourable white collar tortfeasors, represented by the Registrar of the Supreme Court of Canada.

The result is devastating for Canada’s court system. A single administrator is usurping the power of the nine SCC judges. (The SCC considers between 400 and 600 applications for leave to appeal each year.) People think that the judges are too

liberal with the criminals. Such explanation is misleading since the tort was invented by the conservatives, not the Liberal Party. The Registar of the SCC, Mr. Bilodeau, is guarding the key for the “ivory tower” of the nine SCC

judges, just like St Peter the alleged keys of heaven, at least in a popular old belief. You may own a big company that suffered losses in millions of dollars due to federal torts. The administrators of the SCC Registry would stop your appeal as of

right, since you are not a criminal. The Chief Justice needs to find only another judge who sides with the Crown. Then your firm would not get a hearing by the panel of nine judges. If you file an application for reconsideration, the final decision comes –

as it happened in my case – from the Registrar, “In my opinion, your motion does not reveal the exceedingly rare circumstances which would warrant reconsideration by this Court.” The Registrar, who is not a judge, gave the final verdict.

Perhaps this whole streamlining started on Mr. Harper’s birthday in 2006. Maybe he did not want a cake, only favours from four of his ministers to cut some corners. The four cornerstones had sharp corners, indeed. In seven years, the administrators

managed to grind them into ball shape. But how could one build a fortress on such globular keystones? One of the cornerstones was immigration. In 2006, Canada started to enforce two unlawful policies named IP 2 (Processing Applications to Sponsor

Members of the Family Class) and MOU (Memorandum of Understanding). The purpose was streamlining. The cabinet did not care that it resulted in dozens of violated paragraphs of the legislation. These policies decided that, in case of social benefits

paid to new immigrants, the fault was always at the sponsor. Thus, the immigrants and the administrators were always innocent. The mislead sponsors were assured that in case of default they could be heard by a Court – that is not the case. The IP

2 claims that a Sponsorship Agreement and an Undertaking are “contracts” but the sponsors are unaware of that. It’s not in the title. Also, no one has signed those on a minister’s behalf. 132.(4)

of IRPA’s Regulations shows that the sponsors have not signed contracts. By misrepresentation, the ministers call them contracts because then the CRA can garnishee the alleged debts without a ministerial certification prescribed by

s. 146. of IRPA. If your firm signs a document with Canada and later it comes to the Crown’s obligations, it was a vague agreement – without amounts – that was not enforceable. But if it comes to your obligations,

it was a binding contract. The main issues are, in a nutshell, that Canada’s ministers and public servants equate agreements with contracts. Also, they do not differentiate between a “debt provable” and a “debt claim.” The

Federal Court should – but does not – maintain a file about the certified debts of the sponsors. The governing case is Canada (Attorney General) v. Mavi (2011). The judges and their order state many times that the Crown must certify the

debts at the Federal Court, before any garnishment. The Chief Justice agreed with this judgment but when it came to its application in 2012, she put her honourable foot in her honourable mouth, disregarding the verdict. Our ministers openly ignore the

laws of Canada. The cabinet’s money extortion scheme destroys thousands of innocent families, often without gaining much. [The alleged total debt of the family class sponsors is just a fraction of the security costs of Canada’s G-8 Summit

2010.] This is an open rebellion and conspiracy of Canada’s ministers and administrators against Parliament’s will. Perhaps Mr. Harper’s cabinet should propose a new retroactive paragraph, hidden in another omnibus bill, stating that

the laws of Canada are only guidelines that are not applicable for ministers and public servants. (In the author’s case, the federal registries in Edmonton made seven errors in law at seven procedural steps in 2012-3.) If the administrators can

lead our short-circuited country forever, we need only Mr. Harper – often called King Stephen – without paid members of Parliament. If no judges can hear us, we do not need paid judges either. In such hocus-pocus, we should look at the south. In

Brazil, Venezuela and Ecuador, the extreme rightist regimes have lost their credibility and supremacy for good. And, yes, this shift to the centre-left has happened in the US as well. Canada could have such coalition government in 2015 if our conservatives

have no plan to behave and survive lawfully. Mr. Harper has guided his party to the edge of a political ravine. He is just half a step away from it. Every Canadian should urge him to make his last step in the same direction. Roman Emperor Caligula wanted

to appoint his horse as a senator. In Canada, out of the 99 Canadian senators, 52 (!) are appointed by Mr. Harper, our Wg. Hon. Chief Comedian, while the remaining 47 by the previous prime ministers. In November 2013 he pressed the Senate – where his

“bodyguards” were in majority – to get rid of three good but independent senators (Pamela Wallin, Mike Duffy, and Patrick Brazeau) for two years. He closed their e-mail accounts, so the public cannot reach them. Are they in Siberia? This

is Harper’s promised “transparency.” Most Canadians stands with the three victim senators. The Senate was wrong: they should have suspended Harper for two years without pay and could have proposed to the Rt. Hon. Governor General

to appoint the independent Ms. Wallin as Canada’s interim prime minister. (Mr. Harper is the first prime minister since 1867 that has openly turned against the laws of Canada – Parliament’s will – on every level, by massive and intentional

torts.) The Senate should consider changing a few words in our national anthem, by removing “the True North” from it, to make it “Stephen Harper strong and free.” Canada turned into a big circus where, in general, the tails are

wagging the dogs. The criminals are at the top and everyone else is at the bottom of the pyramid. People say that the Pamela Wallin Drive in Wadena, Sask., should be renamed. We agree: it should be called Pamela Wallin Avenue or Boulevard, if not Highway.

Ten or hundred thousands of Canadian businessmen can claim 100% of their private expenses (car, hotel, meals, office in home) as business expenses yearly, without being punished. The border between private and business expenses is not a bright line. Let alone

the 16-dollar orange beverage of ex-minister Bev Oda that has caused her retirement. From the country of the thousand lakes and islands, Canada became the land of one million hypocrites. A federal minister deserves a 16-dollar orange juice if that is its normal

price in her hotel abroad. It is the utmost stupidity to punish a minister for that. Not every Canadian is blind. When an antifascist league or coalition would form the new government in 2015, their first action could be a nationwide

referendum. A question would ask the voters whether (a) they want to dissolve the Senate for good, (b) or dissolve the present Senate altogether but constitute a brand new Senate by democratically elected senators, or, (c) they allow the four parties of the

coalition to appoint over 100 new senators. [For example, the NDP and The Liberal Party each could nominate 52 new senators.] Now the executive power in Canada is controlled by a trio (the A.G., Chief Justice, and

Registrar of the SCC) supporting Harper’s cabinet. They are the cronies of the dictator. They effectively control the Supreme Court, also several registries of the lower courts that easily block the filing of a statement of claim against

the regime. The leaders of any country may successfully copy Canada’s evil recipe how to turn any democracy into dictatorship. The conservatives believe that King Harper is perfect, innocent, and has no idea about these problems, as a victim

of his unruly ministers. The Emperor’s new clothes, written by Andersen, may come to our mind. We may compare the modern social logic of our Canadian leaders with that of the “primitive” Aztecs. The latter could not understand

the reasons of eclipses, while the West and China were much superior in astronomy. The Aztecs originally sacrificed captives during solar eclipses, in order to give a refreshing drink to the darkening Sun, using human blood. They believed that they were

saving mankind by doing that. In contrast, Canada sacrifices the lives of some of its vulnerable sectors of its society. One of them is the innocent sponsors as victims of the government’s fraud. Canada and its government know that many illegal

and immoral things are happening but no one stands up for their protection and democracy. Recently this picture is changing. The author e-mailed the draft of this paper to every second M.P. in the House of Commons (Ottawa), mainly for the opposition.

He received several praising and enthusiastic replies regarding the importance of the issues. Thus, Canada may wake up from its nightmarish sleeping beauty stage before 2015, from her coast-to-coast coffin. LAW AND POLITICS ARE

INSEPARABLE We can place the cabinet’s shuffle of July 14/15, 2013 in historical perspective as part of Mr. Harper’s political engineering. Four of those moves seem to be the results of the instant writer’s latest two court

cases: Rob Nicholson, Jason Kenney, Gail Shea, and Diane Finley ceased to be ministers of the embattled departments. A reasonable person would find it plain and obvious that Mr. Harper was aware of the insurmountable difficulties of the four Crown counsel

involved. He is a good planner. He must have been concerned that his ministers’ conspiracy against the laws of Canada may fail. In order to save face of his corrupt conspirators, he simply gave them new portfolios but kept them in his cabinet.

Any realistic person can see his primary aim that is to gain absolute personal power by ruthless and unlawful means. It seems obvious that his political engineering tries to divert the attention from the criminal charges at the courts developing against

him and four of his ministers. Is he planning with Mr. Nicholson – his minister of defence – to escape overseas by a military plane before the RCMP would try to arrest them? But to which dictator would they flee? It would be absurd to claim

that our federal ministers, judges, and public servants are corrupt per se. However, since 2006, a person or a factor is forcing them to become corrupt and to develop a criminal attitude. First the civil servant, judge or minister is asked to perform

minor favours like cover up the errors of other public servants, ministers or judges, often simply to stay silent and do nothing when a solution or decision is required. Then, the civil servant or judge becomes more compromised, gradually losing his or her

integrity, so it is willing to commit larger and larger crimes for the dictator. Their usual approach is to arbitrarily pick a single paragraph or sub-paragraph from the legislation, then extrapolate it by inserting a few words, or, removing a word from it.

At the same time, they ignore other paragraphs that clearly contradict the misinterpretation of the first paragraph. This method is no other than fraud. If Mr. Harper and his cronies, including Mr. Bilodeau, are right to shortcut or eliminate the panel

of nine judges at the Supreme Court of Canada, the country does not need to maintain that court. Further, if the corruption in the Federal Court and the Federal Court of Appeal are so widespread that involves many judges, not only the chief justices, those

federal courts should be dissolved. (We are not saying that the Supreme Court of Canada does not have three or four judges with integrity that respect Parliament’s will. However, if the independent judges cannot form a majority, the SCC is just like

a Russian roulette where the innocent victims never win.) Investigating corrupt courts may be wasted time. (If you see that your apple has several rotten spots with mould on them, you would not try to save the good part but simply throw the whole apple

to the garbage.) Parliament could order the R.C.M.P. to investigate each court, while cutting 50% of their staff. If each judge needs to write a list of the known unconstitutional errors and biases of every other judge, they would try to save their own jobs

and blame the crooked ones. (There is a good chance that the majority of the judges would mark the names Ms. McLachlin, Mr. Blais, Mr. Nicholson, or Mr. Harper as the sources of the pressure and corruption.) By these means, the R.C.M.P. and Canada could remove

the corrupt judges. As a rule of thumb, the majority of the judges are not corrupt. Usually, the corruption begins at any chief justice. In the instant writer’s case, in the summer of 2013, the order of a judge was patently wrong since she tried

to reinterpret several words of the legislation where a clear interpretation was present. The author appealed her decision. He understands that Madam Justice intended to revise her judgment but the chief judge instructed everybody to simply ignore the appeal.

Such silence is unprecedented in case law in any serious country. It is a good indication of corruption. This example is to illustrate that corruption is detectable. Comparing our top public servants to Bernie Madoff, the latter

person seems much more innocent and sympathetic. He relied on the confidence of investors that were too greedy. He used a financial pyramid scheme. On the other hand, our cabinet is utilizing a political and legal pyramid scheme with torts, pressure and extortions.

Many of our ministers and civil servants take advantage of the fact that our citizens rely on the integrity of Canada as a country. The latter do not suspect that they sign contracts with a bunch of criminals, and that a paper marked “Canada” in

front of them is a fraud. If the R.C.M.P. investigates the criminal charges, our honourable tortfeasors may face longer sentences in jail than Mr. Madoff. Another example is the case of R. v. Critton, 2002 CanLII 3240 (ON SC). In 1971, Patrick

Critton, a teacher, hijacked an aircraft to Cuba. He used a dummy grenade. He was a polite and friendly hijacker. He did not harm or threaten the crew and became upset when money was offered to him He was sentenced to three years imprisonment. Mr. Critton

is much more sympathetic than Harper and his four corrupt ministers with their cruel extortion schemes and terrorist acts. It is a larger crime to hijack a country than hijack a plane. The sentencing of our white-collar criminals should be longer than

the 162-year prison term of the 18-year old Quartavious Davis in Florida. It is a major crime to conspire against a serious country – Canada – and turn it into a zoo using a system of torts and massive corruption. One

cannot deny the genius behind such massive system of federal torts on the websites that define the duties of every public servant. They must obey the ministers while ignore and contradict the nearly perfect laws of Canada. In real practice they obey the actual

policies of the federal ministries that are even more distorted than their written policies. The result is a marked departure from the ideal of “free and democratic society.” Canada has shifted towards a totalitarian dictatorship where the cabinet

can successfully bypass both Parliament [by proroguing it repeatedly] and the excellent judges of the courts. Comparing the tort situation to an electrical circuit, the cabinet ministers have created a parallel second line to the original main circuit and

may make “short circuits” whenever they wish. Is it possible that the days of Canada’s Parliament and its Supreme Court are numbered? Dictatorships do not need good judges only a dozen of yes-men. The courts of Germany could not stop

the Holocaust. If the important issues cannot reach a panel of nine judges, Canada’s court system does not work. A good example is that the Supreme Court of Canada is unable to stop the prosecution of the re-victimized sponsors. Here the sponsors are

victims of a federal tort masterminded by the CIC and completed by the CRA. It is a federal money extortion scheme that helps the provinces. Are the provinces guilty by accepting such gifts due to a federal abuse of power? The readers know the answers

and probably agree on our conclusion that “there is no perfect tort” that could escape punishment forever. LIFE AND DEMOCRACY AFTER HARPER – WITH THE HELP OF QUEBEC Not too many Canadians are familiar

with the upcoming court case, scheduled to Jan. 15, 2014, between the government of Quebec and that of Canada. It is the legal and constitutional controversy about the appointment of Marc Nadon by Mr. Harper to the Supreme Court of Canada. The Quebec National

Assembly condemned Nadon’s appointment in a unanimous resolution. Quebec’s objection is well-founded. Justice Marc Nadon seems to be a puppet and a biased judge that serves the personal interests of Mr. Harper only. He does not represent Parliament’s

will, neither for Quebec, nor for the rest of Canada. He is vague, controversial and unprofessional as a judge. The readers would understand this from the few paragraphs below. The 26 April 2013 Direction of Mr. Justice Nadon, issued by the Federal

Court of Appeal, goes, “I do not see any basis for the acceptance for filing of the material which the appellant has submitted to the Court’s Registry including the Rule 347 Requisition and the Rule 255 Request to Admit. Would you therefore

return all of the material to the appellant as soon as it is convenient for the Registry to do so. “I would point out to the appellant that the only documents that can be filed on the appeal, other than the particular motions are the parties’

respective memorandum of fact and law and in due course the Requisition for Hearing which must be made in accordance with Rule 347 which the Court invites the appellant to read carefully.” Now, the above Direction reveals that its extremely vague

first paragraph contradicts its second paragraph. Thus, Mr. Nadon offers an absolute freedom for the registry personnel what to do. (And many of them, through a pressure from the Court Administration Service – Mr. Gosselin and Ms. Brazeau – are

eventually acting in order to cover up Mr. Harper’s torts.) The oracles of Dodona in ancient Greece were deliberately couched in ambiguous language so that the words could be twisted to correspond to one of several futures. If someone asked, “Who

will win the war?” the oracle might reply symbolically, or phrase the answer in such a way that both sides could argue that it favoured them in battle. Then, whichever side actually won, the oracle could claim prior knowledge of its success. The following

paragraph deal with similar features in the Direction of Mr. Justice Nadon. The laconic and controversial Direction of Mr. Justice Nadon dated 26 April 2013 contradicts itself, due to its vagueness. It fails to identify the individual names of each

document that he wanted to be returned to the appellant author. It does not specify them by their filing dates either. Thus, it would even allow the Registry to return every copy of the Notice of Appeal and the unlawfully mutilated Appeal Book

to the appellant. (The Registry here means the one in Edmonton. The Registry of Calgary has not participated in the torts but always acted fairly.) The hearing before the Supreme Court of Canada on January 15, 2014 will be a turning point in Canada’s

history. In the present lawless state of Canada, Quebec is in the unique position to save the ideal of the “free and democratic society” for the whole country. Quebec should argue not only by the fact that Nadon is “insufficiently

Quebecois” but refer to the unprofessional nature of Mr. Nadon’s previous judgments, his vague and biased decisions. Perhaps Mr. Nadon would be able to find a job at the Small Claims Court of Ottawa but he has not deserved to become a judge of

the Supreme Court of Canada. It seems that he would be unable to show any credential other than Mr. Harper’s recommendation. Clearly, he is far below the level of earlier SCC judges like La Forest, Gouthier, L’Heureux-Dubé, Bastarache, Arbour,

LeBel, Sopinka, Iacobucci, Cory, Major, Stevenson and Binnie JJ., or Lamer C.J. If Mr. Harper is allowed to disobey dozens of laws, Quebec can ignore one law. Thus, Quebec should stand up and warn Ottawa before the trial that their province would cease

to respect any future judgment of the Supreme Court of Canada if Mr. Nadon’s appointment is not cancelled and he is not replaced by their rightful candidate. Quebec has got a window of opportunity to publish such declaration, perhaps till March 2014.

Their province has never agreed to lose the status of a free and democratic society and become subject of a mad dictator comparable to Augusto Pinochet, Ferdinand Marcos, or Nicolae Ceausescu. As Canada’s society has split bitterly between the centre

and the extreme right, now Quebec would make the wisest choice to declare itself a sovereign state before a civil war would break out in the rest of Canada. Quebec has nothing to do with those problems of the other provinces. If the rest of Canada wants

dictatorship, Quebec should not suffer for their decision. Francophone Canadians have voted for a free and democratic society. Our Anglophones preferred a dictatorship. This indicates that Francophone voters are reasonable persons while the rest of Canadians

are treasonable. Originally, victims of torts took their cases to the courts. Since 2006, most of the torts are emanating from the federal courts, or, the court administration service. Worse, Mr. Harper has removed the Hon. Mr. MacKay from his post

in the Ministry of Defence. Canada has lost a well-qualified military leader who is now replaced with Mr. Nicholson that has virtually zero military experience. Right now Canada is vulnerable to any foreign aggression. Our army under the new minister would

be unable to occupy Quebec while controlling a civil war in the rest of Canada. (Query: Did Mr. Harper take the title “Sexiest Male MP” from Peter MacKay and gave it to Mr. Nicholson as part of his new portfolio?) None of the four opposition

parties offer a serious and detailed platform on the Internet, only generic dreams. They promise more possibilities for every Canadian, a better life, more affordable homes and learning but they do not say how. Who will pay the bills? Why do not they promise

to overhaul the Ministry of Injustice and the court system, also reduce the number of corrupt administrators on every level? The country should not pay administrators that keep abusing the laws of Canada. The traitors should lose their jobs and find employment

in factories, stores or other services. A corrupt bureaucrat may become a good nurse or bus driver. The new government would be wise not to touch the existing corrupt court system. The media would sharply attack them, claiming that they want to reduce

the number of forums where innocent victims could be heard. It would be wiser to keep the corrupt judges and chief judges everywhere by now. However, the new government should create a new Constitution Court that would be parallel with the Supreme

Court of Canada. It may belong to the SCC but under an independent Chief Justice that would report directly to Parliament, not to a minister. Such Constitution Court would be a healthy alternative. Canada is a capitalist country and the essence of

that system is competition, not state monopoly. Without elected judges, Canada cannot be called a free and democratic country. If every second PM is corrupt at a certain point, and each of them appoints a puppet judge or two into the SCC, the latter court

would become like a kangaroo court of a banana republic, sooner or later. Mr. Harper may sacrifice Mr. Gosselin, Madam Justice McLachlin or Mr. Justice Blais and appoint new, independent and unbiased chief judges. However, our inefficient court system may

still have a cancer-like incurable illness. Therefore, the four opposition parties could easily agree upon a common platform that promises more justice to every Canadian, by a new Constitution Court. It is plain, obvious and undeniable that our

present federal courts and the Supreme Court of Canada cannot answer many constitutional questions. Dozens of Canadians may pose hundreds of such good questions yearly but the courts are deaf and inefficient. There are too many cases and no answers. The opposition

parties would gain a landslide victory by such promise. They cannot go wrong with that. On the other hand, we have a nearly perfect RCMP where corruption is rare. The police side with the laws and society. Also, Canada has thousands of lawyers that

are exceptionally good. The writer of this paper has met many Canadian lawyers in several provinces. All of them were knowledgeable professionals with integrity. None of them wanted to cheat him or to take advantage of him. If Canada has such a treasure, the

best lawyers of the country could become judges of the new Constitution Court. The most plausible solution would be to rely on the bar associations of each province. Each of those associations could elect, say, two of their best members and nominate

them as judges to the Constitution Court. Such court may have 13 or 15 members that hear each case by videoconference. When some of them would take a vacation or become sick, the other judges would be active. There would be no appeal from their decisions.

Most Canadians are laughing when they talk about North Korea and its silly dictatorship. They consider the North Koreans as dummy people that love their ruler blindly and unconditionally. They do not realize that Canadians are in the same boat. We cannot

see that our media deceives us. Our major newspapers and TV programs serve the richest 1% of our country. That upper class lives in the misbelief that the more suffering of an average Canadian means more profit for them. Increasing oppression and poverty does

not increase their wealth per se but makes them less rich. It may take decades for them to understand the truth in the correlation. The rest of the media – including the smaller newspapers and radio stations – starts to wake up

and realize the extreme risks of this country. You can read very good articles, almost daily, regarding the shifting and tilting of the Conservative Party. For example, “Party tilts right as PM faces scandal” or “Hard-core shit to the right.”

The Conservative party have many outstanding politicians. We may expect some of them crossing the floor in the House of Commons, perhaps even before the assassination of the writer. As an average Canadian citizen, the writer is anxious to see some

political development of harmonizing the laws of Canada – that is Parliament’s will – with the (widely unlawful) policies of the present cabinet. If the instant policies of our federal ministers are correct then the laws of Canada need a

complete overhaul, perhaps the Charter should be declared invalid, and the federal legislation would become only a rough guidelines that is always overruled by the decisions of the federal ministers. One cannot have a carriage that goes both forward

and in reverse at the same time. Or, if two horses are pulling it into two opposite directions, it would soon break apart. In our case, that fragile carriage or chariot means Canada. If the people of Quebec would prefer to jump out of such collapsing vehicle

we cannot blame them at all. When the US is in a crisis, the American president closes his speech by the words, “God bless America!” For half of Canadians, that may mean, “Steve keep our land glorious and free! O Canada we stand on

guard for thee.” But the guards are sleeping so perhaps this article as a humble alarm clock would be appropriate at the right moment. REFERENCES [Canada’s policies IP 2

and MOU] http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/resources/manuals/ip/ip02-eng.pdf and http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/department/laws-policy/mou/ [Canada’s laws] http://www.canlii.org/en/advancedsearch.html & http://laws.justice.gc.ca/eng/ Cassels,

J., & Adjin-Tettey, E. (2008). Remedies: The Law of Damages. Toronto: Irwin Law Inc. Certified Questions – Immigration and Refugee Protection Act. (Updated on June 4, 2013.) Web. Fine, S. (2013). Quebec politics:

PQ to make case before Supreme Court against appointment of Marc Nadon. Toronto: The Globe and Mail. October 31, 2013, Page A3. Furmston, M. P., Cheshire, G. C., Fifoot, C. H. (2007). Cheshire, Fifoot & Furmston’s Law of

Contract. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. Gosman, E. (2000). Revelan una poderosa red de narcotráfico en Brasil. (In Spanish.) São Paulo. http://edant.clarin.com/diario/2000/12/07/i-03201.htm I.R.P.A.

(2013). Web. http://www.cba.org/CBA/advocacy/pdf/immigration-refugee.pdf Stokland, E. (2003). Brazil: Alone against the death squads. Amnesty International. Web. Waddams, S. M. (1997). The Law of Damages. Toronto: Canada Law

Book Inc. P.S.: For PDF files of the court orders and directions please contact Zoltan Andrew SIMON by e-mail: zasimon@hotmail.com [Many of them are not available by www.canlii.org]

AN IGNORED AND PENDING MOTION IN THE SCC:

Notice of Motion to the Chief Justice or a Judge to state a Constitutional Question Court File No.: _______________

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF CANADA (ON APPEAL FROM THE FEDERAL COURT OF CANADA)

BETWEEN: ZOLTAN ANDREW SIMON Appellant, Applicant to this Notice of Motion (Also

appellant in the FCA) and HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN IN RIGHT OF CANADA Respondent (Also respondent in the FCA)

Notice of Motion to the Chief Justice or a Judge to state a Constitutional Question or Questions Filed by Zoltan Andrew Simon, Appellant as of right pursuant to s. 61.

of the Supreme Court Act

Ms. Jaxine Oltean, Counsel

Zoltan Andrew Simon, Appellant Department of Justice Canada

(Applicant to this motion) Prairie Region, EPCOR Tower,

72 Best Crescent (new address) 300, 10423 – 101 St., Edmonton, AB T5H 0E7 Red Deer, AB T4R 1H6 Phone: (780) 495-7324; Fax: (780) 495-8491 Phone: (403) 342-8826 (Home/ Landlord) E-mail:

jaxine.oltean@justice.gc.ca Phone: (403) 392-9189 (cell.) Fax: (403) 341-3300 E-mail:

zasimon@hotmail.com TABLE OF CONTENTS Notice of Motion to the Chief Justice or a Judge to state a Constitutional Question

1 Memorandum of argument of the appellant, applicant to this motion

4 Part I: A concise overview of the appellant’s/applicant’s position with respect to issues of public importance that are raised in the Notice of Appeal; a concise statement of facts

4

Part II: A concise statement of the questions in issue

6 Part III: A concise statement of argument (with paragraph numbers

of legislation) 10 Part IV: Submissions in support of the order sought concerning costs

12 Part V: The orders sought, including the order or orders sought concerning costs 13

Part VI: Table of authorities alphabetically, with paragraph numbers of law 13

Part VII: Photocopies of relevant provisions of statutes, regulations, rules and case law: 15 Constitution Act, 1982 (Part I: Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms)

15 Courts Administration Service Act,S.C. 2002, c. 8

20 Criminal Code,R.S.C., 1985, c. C-46

22 Federal Courts Act, RSC 1985, c F-7

28 Federal Courts Rules, SOR/98-106

33 Financial Administration Act, R.S.C., 1985, c. F-11

35 Guidelines for Preparing Documents to be Filed with the Supreme Court of Canada (Print and Electronic)

– an older version of the present website http://www.scc-csc.gc.ca/ar-lr/gl-ld2014-01-01-eng.aspx#D1b

38 Interpretation Act, RSC 1985, c I-21

44 Rules of the Supreme Court of Canada, SOR/2002-156

47 Supreme Court Act, RSC 1985, c S-26

53 CASE LAW:

Apotex Inc. v. Canada (Health), 2012 FCA 322 (CanLII)

62 Krpan v. The Queen, 2006 TCC 595 (CanLII)

64 Meldrum v. Public Trustee of The Province of B.C., 1998 CanLII 5563 (BC SC) 66

Zoltan Andrew Simon v. Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, [2012], SCC 34831 69 Zoltan Andrew Simon v. Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada [May 30, 2013],

Docket: A-367-12 [Federal Court of Appeal]

70 APPENDIX: Documents, including an affidavit that the applicant intends to rely on 75

The appellant’s (here applicant’s) affidavit

75 Exhibit 1: Z.A. Simon’s Notice of Appeal cover page to the SCC, received March 9, 2012 76 Exhibit 2:

Letter of Mary Ann Achakji (SCC Registry) dated March 28, 2012 77 Exhibit 3: Letter of Barbara

Kincaid (SCC Registry) dated May 24, 2012 79 Exhibit

4: Zoltan A. Simon’s letter to Mr. Roger Bilodeau (Registrar) dated June 4, 2012 80 Exhibit 5: Front (style of cause) page of Applicant’s Motion of Reconsideration of

Application for Leave to Appeal, received by the SCC Registry on Oct 25, 2012 82 Exhibit 6: Letter of Michel Jobidon (SCC Registry) dated October

30, 2012 83 Exhibit 7: Letter of Roger Bilodeau (SCC Registrar) dated December 18,